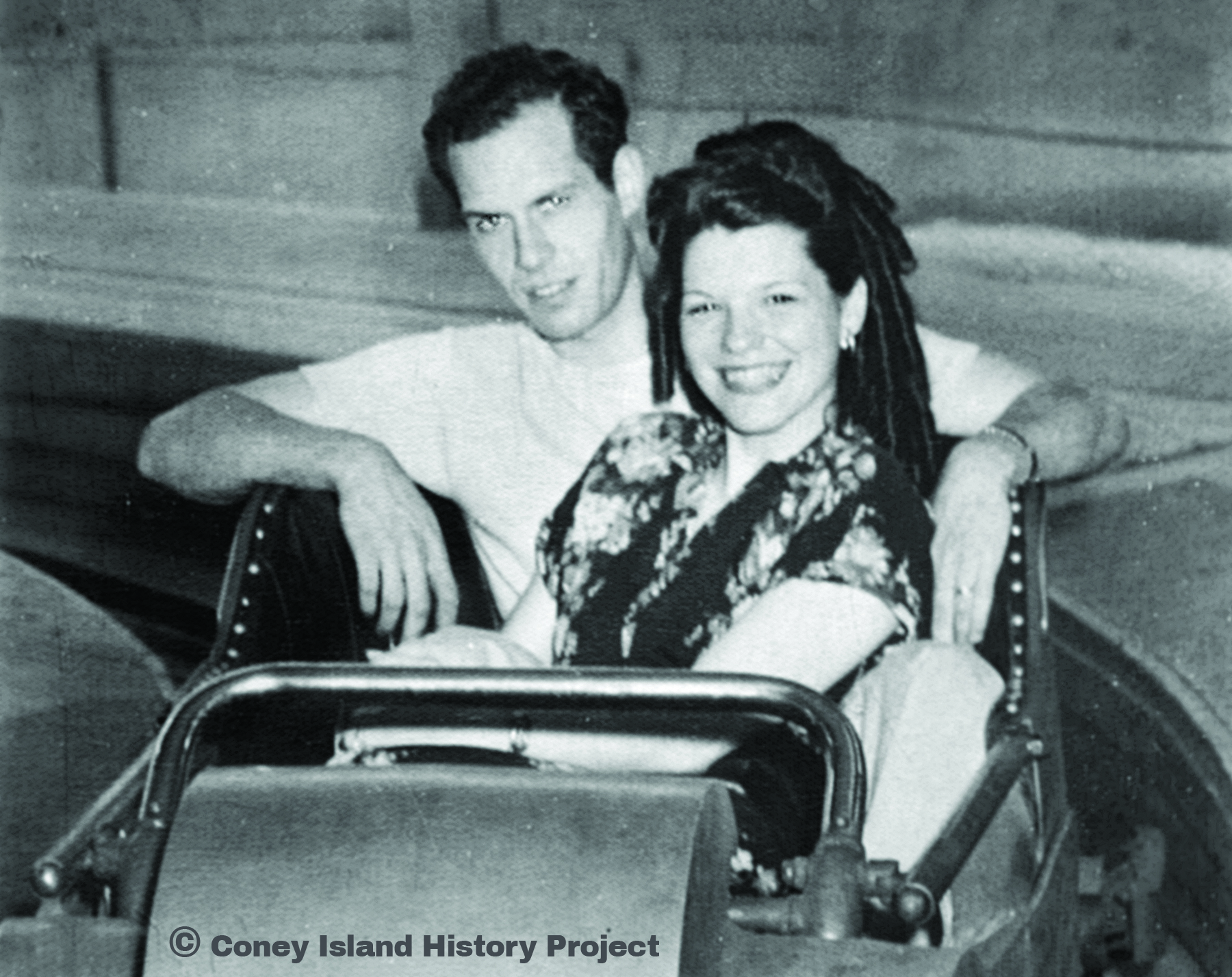

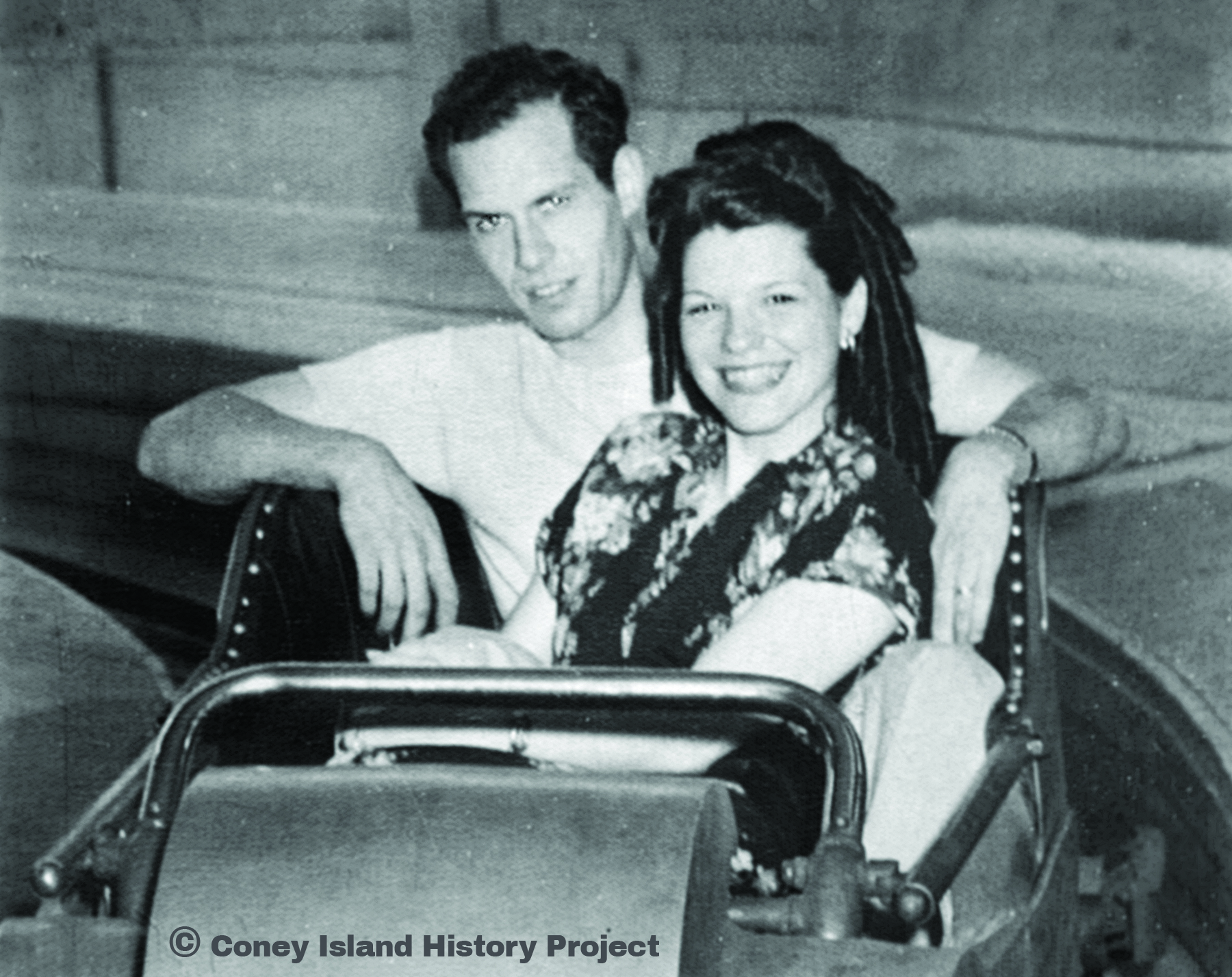

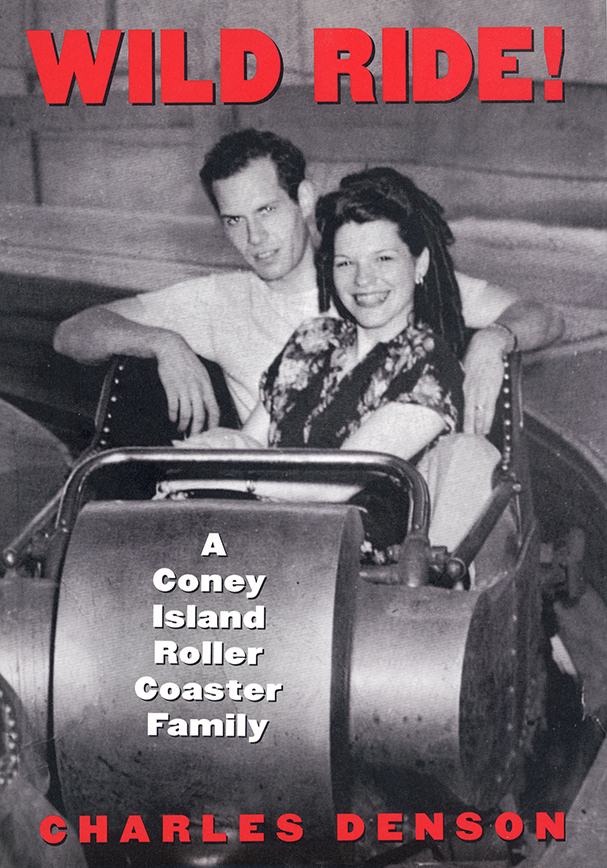

John and Louise Bonsignore on the Bobsled, 1940s.

Louise Bonsignore passed away on October 10, 2025, at the age of 99, just shy of her 100th birthday. Louise, and her late husband John, were Coney Island royalty, and the subjects of my book Wild Ride! A Coney Island Coaster Family, which tells the story of the Bonsignore family’s dramatic history in Coney Island.

Louise was sweet, kind, caring, and incredibly generous. She had a smile that could light up the world. And what a voice! She was one of a kind, a talented opera singer and patron of New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Luciano Pavarotti adored her.

The Bonsignore family once owned and operated the Bobsled coaster, the L.A. Thompson Scenic Railway, Stauch’s Baths, The Tornado Coaster, Silvers Baths, and many other properties in Coney Island and Brighton Beach. They were a major force in Coney Island, from the 1920s to the 1970s.

John and Louise raised their family in a three-story brick building ensconced below the last turn of the L.A. Thompson Scenic Railway on West 8th Street, a structure that had once been the office and workshop of LaMarcus A. Thompson, inventor of the roller coaster. Their historic house and coaster were lost to urban renewal and demolished in 1954.

Everything about Louise was operatic. It was impossible to visit the Bonsignore home in Manhattan Beach without being asked to stay for a six-course dinner prepared by Louise: stylishly dressed, perfectly coiffed, and wearing her trademark stiletto heels. Louise made you feel at home and part of the family. The house was always filled with interesting people and pets, food and wine, and amazing Coney Island stories.

With Louise’s passing, a 100-year-history of Coney Island comes to an end, but will not be forgotten. The love she gave lives on.

Here is an excerpt from Wild Ride:

Louise Corona was a beautiful girl with old world manners, a serious girl with bright eyes and a beautiful smile. She wore the finest clothes in the latest fashions, all created by her mother and father. Her father was a custom tailor who made suits for Brooklyn’s wealthy and stylish “men of honor,” and her mother was a seamstress who did all the handwork for Henry Bendels in Manhattan. Her grandparents left Naples in 1901 and settled in Coney Island on West Third Street in a tight-knit neighborhood of small frame houses alongside Coney Island Creek. It was a melting pot of Italian, Irish and Jewish families. Small truck farms and chicken coops still lined the streets.

Her family was cultured and Louise studied voice with her aunt and uncle who taught opera in Manhattan. “They had been brought to America by Toscanini,” she recalls. “I had a good voice and they gave me lessons, they coached me from childhood.” Louise was known for her angelic voice. At the age of thirteen, accompanied by her aunt, she gave her first public performance at a USO concert at the Jewish temple on Ocean Parkway. The orchestra was amazed at her ability to hit the high notes.

John and Louise moved into an apartment in the Thompson house, his childhood home under the roller coaster, and they began raising a family. Louise remembers the odd living conditions in the house below the coaster just before they finally moved out. The house was also a workshop. “In our basement were tracks where the Thompson ride could come in so that they could do repairs on the cars. It was a shop where they could do any kind of repair that they needed to do. We also had a carousel stored down there that my uncle, Pete Paluso, had bought and was looking to re-sell.

Soon the couple had three children and grandpa Joe began what became a family tradition on the L.A. Thompson. Every morning, before the coaster opened to the public, Joe would take the first ride and wave to his grandchildren gathered at the window as he rode by. “He’d wave to us with a big grin on his face and the children would wave back.” Louise remembers. “ He was so happy with that first ride.”

- Charles Denson

Louise Bonsignore, 2006. Photo by Charles Denson

Louise on the Bowery in front of the Bobsled, 1940s

Charles Denson and Louise Bonsignore, looking lovely at 98 years old.

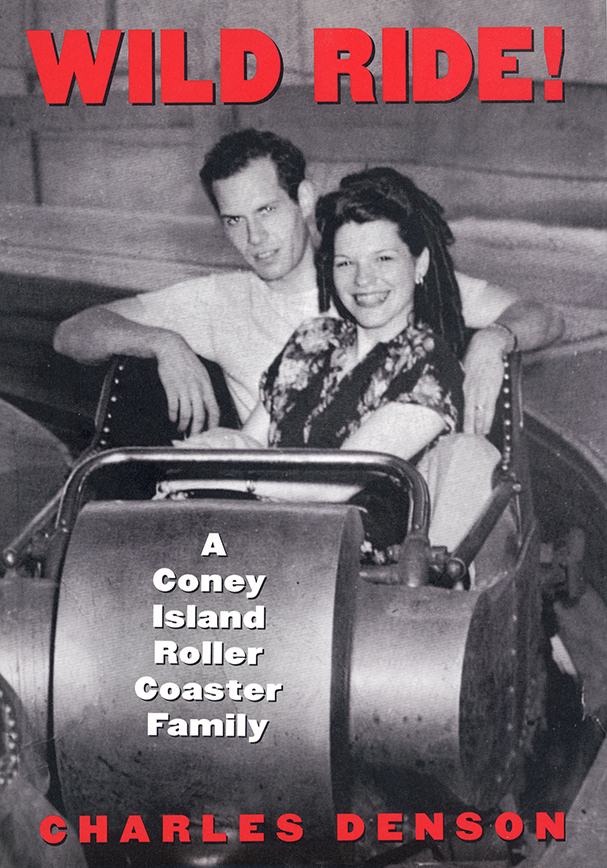

Wild Ride: A Coney Island Roller Coaster Family, by Charles Denson.