This interview was conducted and recorded in Cantonese Chinese by (Sylvia) Ching Man Wong. Transcription by Ching Man Wong and Keenan Yutai Chen with English translation by Keenan Yutai Chen. Read the transcript and translation below:

這一段用廣東話進行的訪問是由王靖雯完成和錄音,並由王靖雯和陳毓泰完成中文抄本。而英文翻譯則是由陳毓泰完成。以下為錄音文本和英文翻譯:

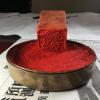

Calligraphy artist Lu Zhao was born in 1942 in Toishan in China’s Guangdong Province. He immigrated to New York in 1989 and lives with his family in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. Mr. Zhao says that his path to mastering calligraphy began as a five-year-old and he started painting portraits when he was eight. His first teacher was Jinyu Zhao, a member of his extended family who taught him to write on scrolls, choose copybooks, and the relationship between paper, brush and ink.

書法家趙魯先生於1942年出生於中國廣東的台山。他在1989年移民美國,以後便與家人一起布魯克林的賓臣墟居住。除了在5歲的時候便已開始學習書法,趙先生稱他還在8歲的時候開始學習繪畫。他的書法啟蒙老師是一位名叫趙进裕的遠房親戚。在這名老師的教導之下,趙先生學習到如何在横批上書寫和如何選擇字帖、以及紙、筆和墨三者的關係。

Growing up in a poor family, Mr Zhao recalls setting aside money he earned from painting portraits to buy art supplies. During the Cultural Revolution, art schools stopped holding entrance exams. “I could only study on my own, that was it.” He says that he followed the example of Wang Mian, a Yuan dynasty poet and painter who “was raising cattle but somehow taught himself to paint plum blossoms.” After high school, Mr. Zhao made a living teaching Chinese literature, calligraphy and painting, and joined various calligraphy societies in China. In New York, he worked as a painter for hire, as well as in restaurants and garment factories, to support his family.

由於出生貧苦,趙先生稱他將幫他人繪畫肖像画中賺取的報酬儲蓄起來,用來購買美術創作所需要的用具。由於藝術學校在文化大革命的期間停止了入學考試,他回憶起:「所以只能逼自己自学,就是这样」。趙先生稱他以元朝是人和畫家王冕作為榜樣,因為王冕雖然白天放牛,但仍然能夠自學繪畫梅花。而在完成高中學業以後,趙先生除了擔任中文、書法和繪畫老師以外,還參加了眾多的書畫協會。而在移居紐約以後,趙先生除了在餐館和製衣廠工作以外,還繼續通過繪畫賺取酬金,用於幫補家庭。

In 2015, a story and video about Mr. Zhao volunteering to create the funeral scrolls for Police Officer Wenjian Liu was featured in the New York Times and brought him acclaim. Liu and his partner Officer Rafael Ramos had been shot and killed while sitting in their patrol car in Brooklyn. “I regard him (Officer Liu) as a Chinese national hero,” says Mr. Zhao, who participated in exhibitions honoring extraordinary people during his high school years. “I have been admiring national heroes since I was a kid and showing a lot of respect for them.”

在2015年的時候,《紐約時報》用文字和影片報導了趙先生如何為殉職的紐約市警員劉文健義務地創作哀輓聯的故事,受到了外界的讚揚。劉文健和他的搭檔拉莫斯當時在布魯克林巡邏,是坐在警車內被射殺的。而在高中時期參與了很多优秀人物展览的趙先生說:「我们觉得他(劉文健)是中华民族的英雄」。他補充到:「我从小对英雄人物都比较崇拜,給予很大的尊重」。

His calligraphy and paintings are in the collections of the White House, Harvard-Yengching Library, Songshan Shaolin Temple and Deqing Museum in Huzhou, Zhejiang, among others.

他的書法和繪畫作品被白宮、哈佛大學燕京圖書館、嵩山少林寺和浙江省德清博物馆等多所機構收藏。