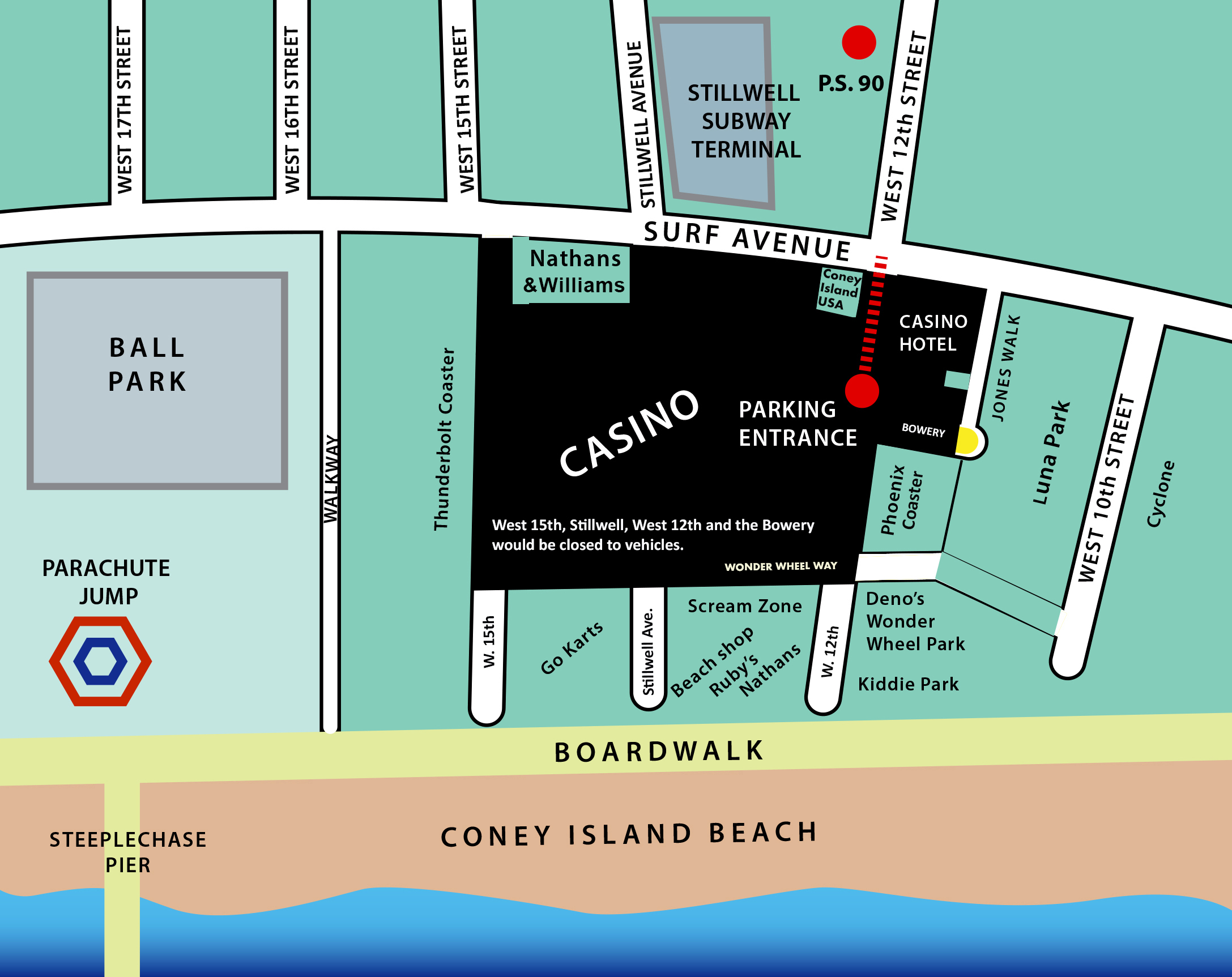

Developers of "The Coney" casino want to close West 12th Street to emergency responders (above). Photo by Charles Denson

Developers of “The Coney” casino have proposed a plan that will endanger the lives and safety of millions of visitors who come to Coney Island every summer. Coney Island is a seasonal outdoor attraction for people from all walks of life who come to enjoy free access to the ocean, beach, and Boardwalk. The developers recently revealed their scheme to close and “demap” the three main streets in the amusement zone that connect Surf Avenue to the oceanfront.

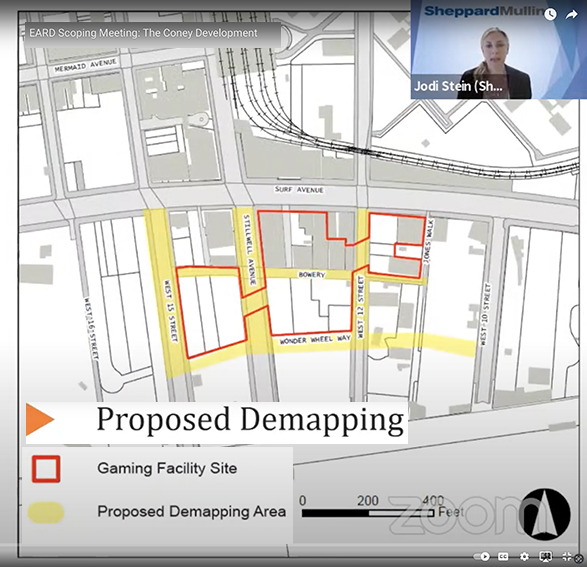

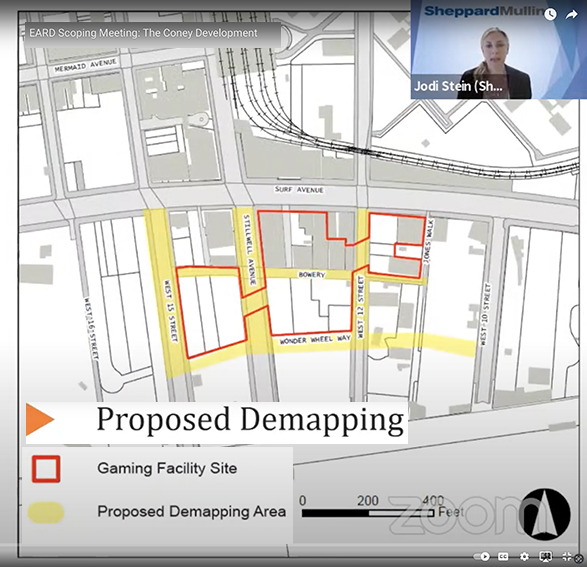

The casino consortium made their plan public during a Zoom presentation to the City Planning Commission on June 27. They're asking the City to transform these crucial city streets into “landscaped pedestrian walkways” for the benefit of the casino and their adjacent 40-story hotel. This is a dangerous land-grab of epic proportions.

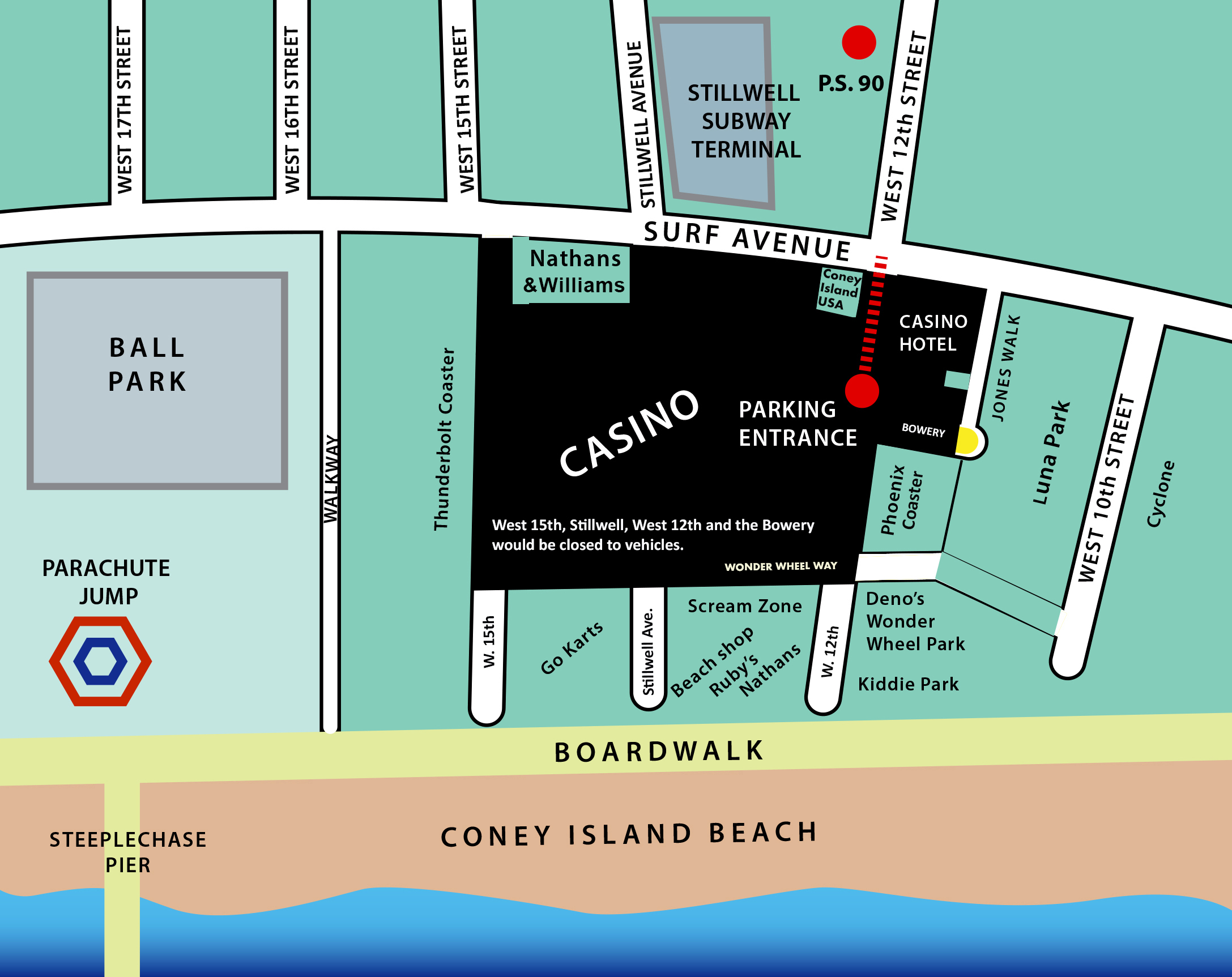

The streets that the developers want to take for the casino serve as designated “fire lanes” used by emergency vehicles such as fire trucks, police vehicles, and ambulances. If the City approves this plan, there will no longer be direct emergency access to the beach, Boardwalk, or amusements for nearly a quarter-mile stretch of the world’s most crowded beachfront.

Lacking direct access, firefighters would be forced to drag hoses for long distances to battle a fire. Medical personnel would have to roll stretchers from gridlocked Surf Avenue to reach those in need of medical attention on the beach, Boardwalk, or rides. Ladder trucks would be unable to perform rescues should a ride break down.

Millions of visitors will be put at risk if this dubious plan is approved. First responders need these access points in order to save lives. Losing vehicular access to these streets will increase response time, and lives will be lost.

Closing the streets would also limit disability parking and wheelchair accessability to the beach and Boardwalk, a clear violation of federal ADA Accessibility Standards. Amusement parks and local businesses will have their deliveries blocked, and repair vehicles and utility trucks will no longer be able to service any businesses south of Surf Avenue.

The casino demapping plan proves that the developers have no interest in public safety and no knowledge of how these streets are used. It seems as if they want to kill all the existing businesses surrounding the proposed casino. And they don’t seem to care if the rest of Coney Island burns.

The street closure would also eliminate 160 public parking spaces and transform West 12th Street into a short driveway leading to the casino’s private 1,500-car parking garage. Vehicles entering and exiting the casino garage will create a choke-point at the already overcrowded intersection of Surf Avenue and West 12th Street.

A fact ignored in all the studies and comments regarding the casino is that a nearby public school will be heavily impacted by the casino. Public School 90 is located on West 12th Street, a block north of the proposed casino. When casino traffic gridlock backs up on West 12th Street, it will have a negative impact on the school, and cause delays for parents who use cars to drop off or pick up their children at the school.

The reason for this oversight is that the City Planning Commission only studies a 400-foot radius surrounding the proposed casino, and P.S. 90 is located just beyond that radius. The safety and well-being of hundreds of young students is being ignored.

It is obvious by any measure that Coney Island is the wrong site for a massive casino-hotel project. The negatives, of which there are so many, outweigh any of the “pie-in-the-sky” benefits promised. Simple arithmetic should convince elected officials that this location will not provide the revenue or jobs that the State and City of New York expect from a casino project.

Stillwell Avenue, West 12th Street, and West 15th are vital to the life of the amusement zone and must be kept open. These streets were cut through to the ocean in the 1920s when the beach was still private property. The City built these thoroughfares to provide access for the public to enjoy a free beach and Boardwalk.

Now the developers of “The Coney” casino want to reverse a century of free public access by privatizing public property in order to funnel visitors into an ill-conceived casino project.

This demapping plan is extremely dangerous and detrimental to all who visit Coney Island or call it home. It must be rejected.

- Charles Denson

This illustration shows the massive footprint of the proposed casino. Stillwell Avenue, West 15th Street, and West 12th Street would be closed to traffic. The developers have also asked the City to demap The Bowery and Wonder Wheel Way. There would be no vehicular emergency access to the beach and Boardwalk between West 10th Street and West 21st Street. Public School 90, located at top of map, would be severely impacted by the "The Coney" casino. Map by Charles Denson

P.S. 90 is located on West 12th Street, near the entrance to the casino's proposed 1,500 car garage. For some reason, the casino's impact on the school is being ignored. Photo from P.S. 90 website

An ambulance on West 12th Street at the Boardwalk. Developers of "The Coney" casino want to close the street to first reponders. Photo by Charles Denson

Fire trucks and ambulances on West 12th Street. This street is a fire lane that developers of "The Coney" casino want to close to build a casino. Photo by Charles Denson

The Casino's lethal plan to take over the amusement zone's streets was revealed in a June 2024 scoping meeting on zoom. The clueless attitude of "The Coney" casino developers and their consultants and lobbyists show a blatant disregard for the lives of visitors and residents in Coney Island. Screengrab from casino presentation at NYC Department of City Planning EARD (environmental review) Scoping Meeting https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1T0IJBft4Rw