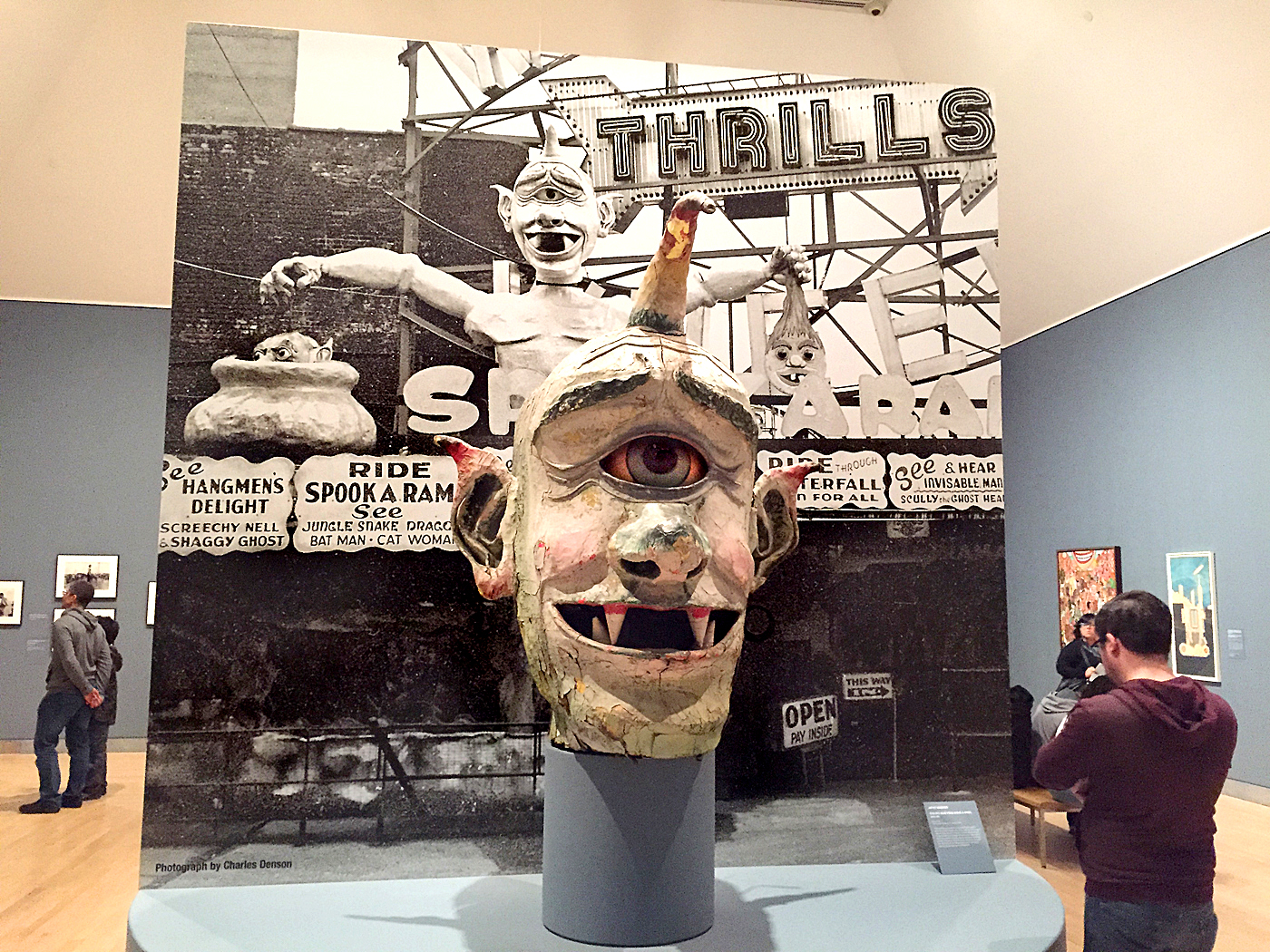

Astroland's Astrotower Photos by Charles Denson

What's in a name? It depends. I've been asked my opinion about naming new Coney Island attractions after old ones, specifically the name "Astrotower," which is being co-opted by Luna Park to use on their newest ride. The other names in question are Luna Park, Thunderbolt, Steeplechase, and Feltmans. In theory it shouldn't matter, and if it were anywhere else but Coney Island, few people would care. These names, however, carry a lot of weight because of the dramatic way in which they met their demise.

The original Luna Park and original Feltmans were failed businesses when they ended their long runs. And there were reasons for their failures. They had outlived their glory days and, like other older attractions, failed to change with the times. Luna Park is a generic name that was used all over the world. Coney's original 1903 Luna was actually named "Thompson & Dundy's Luna Park." The founders were proud of their creation. I could never figure out why Zamperla didn't add their own name to the new park — it was as if they were embarrassed by it. Using a new name or adding a twist to the name would have been a step forward instead of a confusing step backward. The media and the public are often confused as to whether the old and new parks are the same.

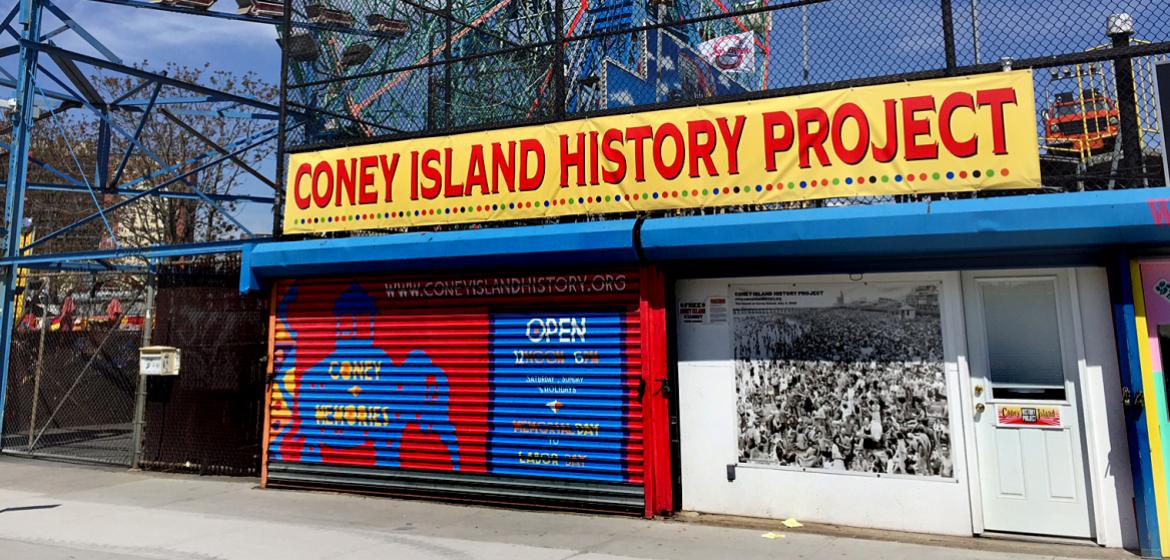

In 2010 Zamperla USA President Valerio Ferrari told the New York Daily News that he decided on the Luna Park name after "devouring" my book, Coney Island Lost and Found. I didn't think reviving the name was the best idea, but in the end it didn't really matter, as Coney Island seemed to be moving forward. At the time, the Coney Island History Project put together an extensive, celebratory exhibit about Luna Park history and I wrote an op-ed piece in the Daily News about how beautiful and exciting it was to see the spectacular lighting on Luna's new entrance. I was no fan of Luna's corporate mindset but I was curious to see where it would go and we welcomed them.

Valerio was friendly and gave me free rein to document the park's construction, but that soon came to an end. When Luna Park tried to evict two historic businesses on the Boardwalk, I was interviewed by the Wall Street Journal and frankly expressed my displeasure. Valerio was pissed off and told me that I was "too loud." I had to remind him that I didn't work for Luna Park, and that to me it was personal, not business. These Boardwalk people were my friends and their livelihoods would be ruined. I realized that the city's plan for a single operator was in the works and that this was the beginning of a process to wipe the slate clean. I had little to do with Luna Park after that. Following a public outcry, the two businesses were allowed to stay and were given new leases.

As far as using the Feltmans name, the only thing I can say is that if you're actually making the greatest hot dog in the world, a new and delicious product, then why not put your own family name on it? Be proud of your accomplishment and write a new chapter! Publicity and competition with Nathans can only take one so far.

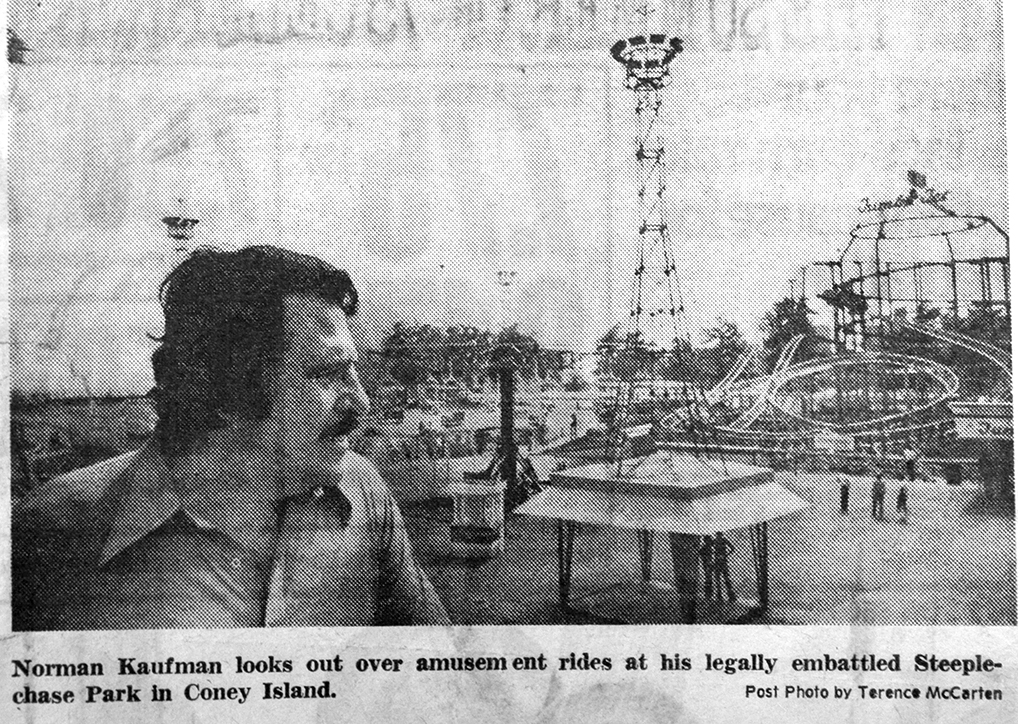

There is an inherent problem with naming new attractions after old if you are not truly reviving the original but just copying the name. Renaming is a reductionist ploy that doesn't honor or pay tribute to something historic. Steeplechase, Thunderbolt, and Astrotower were all destroyed in horrible ways that are still traumatic to anyone who knew the real thing.

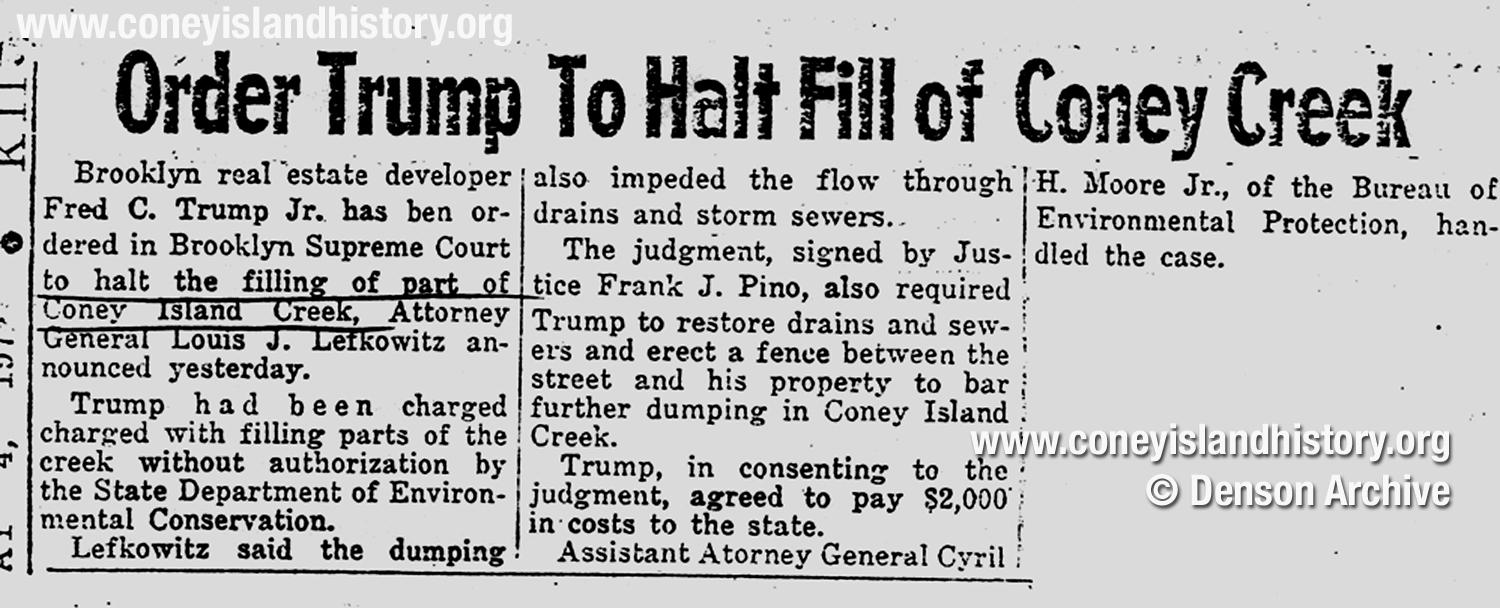

Fred Trump's sadistic demolition of the Steeplechase Pavilion, which included partygoers hurling bricks through the stained glass windows of the pavilion, is still a horrifying memory to those who loved the place. It's kind of creepy to see the name tacked onto a ride that has no relation to the original. It makes no sense.

The Thunderbolt Roller Coaster was ordered demolished by Mayor Giuliani, who repeatedly lied about his involvement until forced to admit under oath in court that he personally and illegally gave the orders. It was a real abuse of power, and the demolition still brings up bad memories of the stubborn battle between owner Horace Bullard and the authoritarian mayor. I wrote the last-minute landmark application for the structure and remember the Landmarks Preservation Commission's refusal to even look at it. Whether you loved or hated the old ruin, it should not have been illegally demolished. The reproduced signage on the new coaster is a constant reminder of abuse of power in Coney Island.

The new "Thunderbolt" coaster uses the name and signage, but where's the old hotel below it? The old Thunderbolt was special: historic and eccentric, expressing the quirkiness of the real Coney Island. The new tubular coaster is a great attraction and people love it, but what does it have to do with the original? Nothing! Why not come up with a new name? Putting an old picture of the real T-Bolt in the ticket box is a nice touch, but it has no context and context is everything when it comes to history.

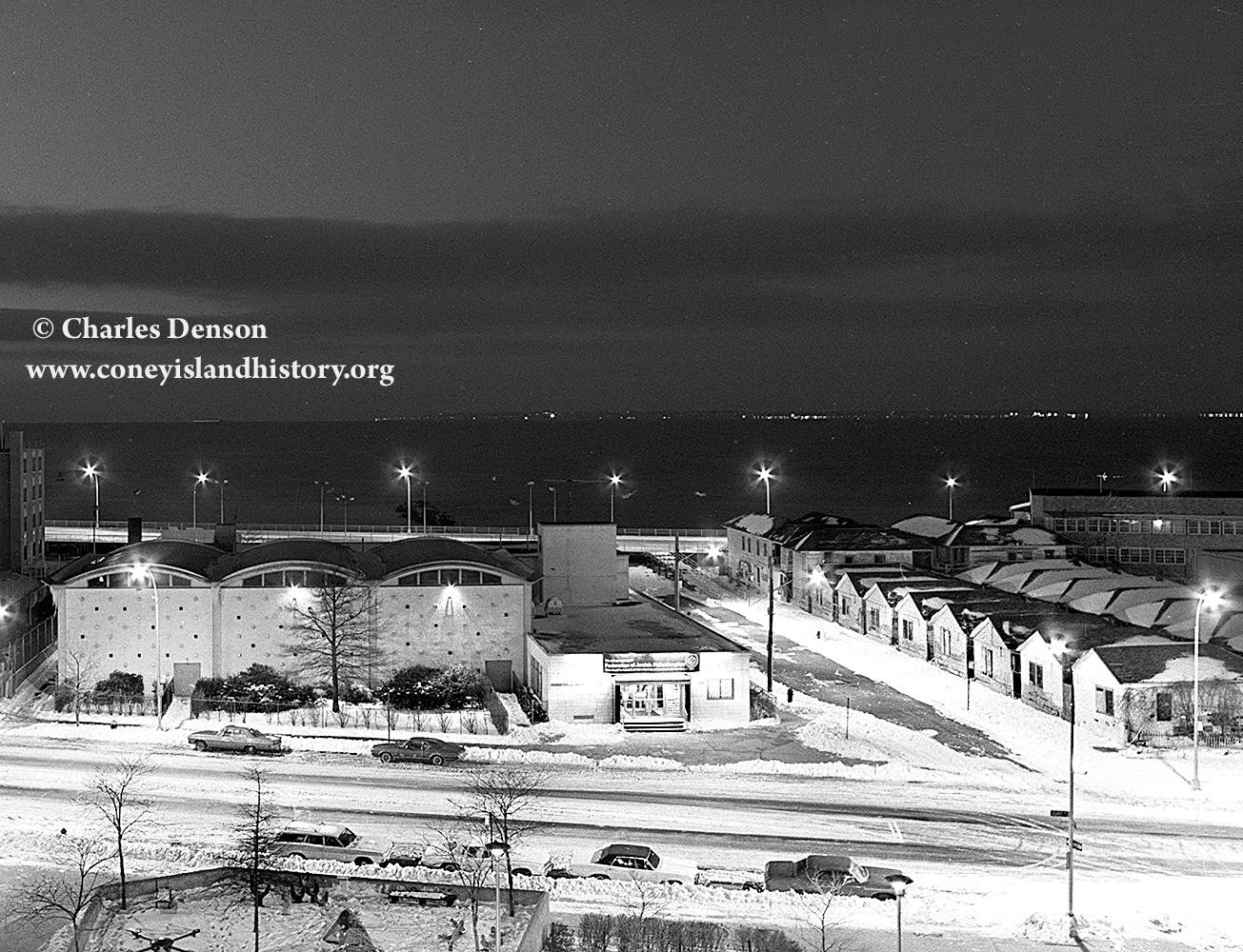

That brings us to the Astrotower. You don't have to be an old-timer to recall what happened to that landmark. The wounds are still fresh, and the city's condemnation and demolition of the tower was a Fourth of July fiasco that will go down in infamy. There is no need to detail the bizarre events that led up to the dramatic emergency dissection of the beloved Astroland icon, but it should be obvious that using its name for another attraction is kind of tone deaf and antagonizes those who feel that it's inappropriate. The general public may not care because, after all, they come to Coney for fun, not to dwell on the past or politics. Many think it's not a big deal. I told Luna that using the Astrotower name was not a good idea and that I was not the only one who felt that way. Carol Hill Albert, whose late husband built the original tower, was not too happy about it either. There are other creative ways to pay homage to attractions from the past.

Sometimes it's better to leave something alone. You can dig up a corpse but it's impossible to bring it back to life. It's called grave robbing and just makes a mess. There's a good reason that you don't see many new cruise ships named "Titanic."

Childs Restaurant, B&B Carousell, Cyclone, and Parachute Jump all represent real history as well as the future, and Zamperla controls three of these landmarks. Isn't that enough? Luna Park has given the public a slick and exciting ride showroom with a beautiful gate. The old Luna was about exotic fantasy architecture and "weird whimsy." The new one is more about business and efficiency.

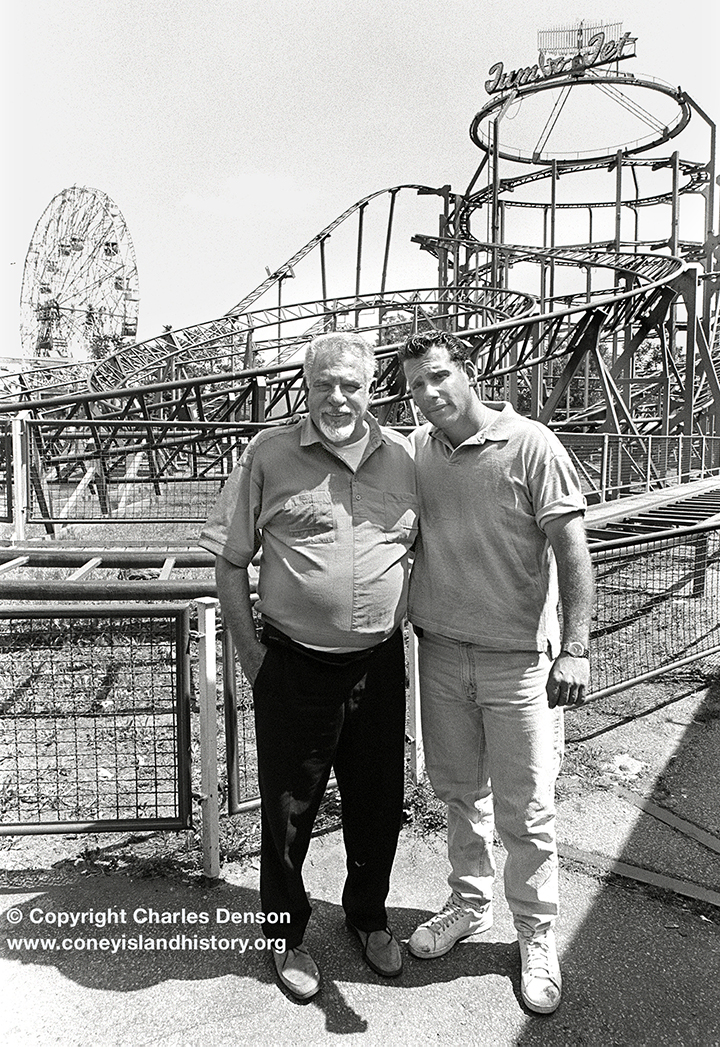

A couple of months ago I was approached by the new management of Luna Park after Valerio Ferrari left the company, and invited to sit down with them to discuss history. We had a long, cordial meeting. I also spoke with their branding consultant and gave my unbiased opinion about Coney Island's future. It seems as if they're open to new ideas. I'm not big on corporate environment and feel much more comfortable and at home at Deno's Wonder Wheel Park, with it's family dynamic and historic atmosphere — to me that's the authentic Coney Island that I grew up with.

Context is an important component to history, and learning about the past does not have to be academic. The Coney Island History Project's stated mission is not about nostalgia, which is longing for a past that never was. We're interested in what endures and why, and how it will work in the future. I hope that the Boardwalk leases will be renewed. I hope that the old businesses that have endured will survive and work together to preserve Coney's heritage while moving into the future. That would be truly historic.

– Charles Denson

UPDATE:

I was encouraged by the dialogue generated by my story about nostalgia. I'd like to add a simple example of a successful way to honor Coney Island History. That would be Coney Island USA's Mermaid Parade! This beloved annual rite harkens back to the old Coney Island Mardi Gras, a tradition that defined Coney Island for half a century before coming to an end in 1954.

When CIUSA revived the idea of a parade, a new name and theme were chosen and they created a magical event with roots in a long-gone Coney Island ritual. There was no recycling of a name from the past. The media recognizes the origins of the Mermaid Parade when reporting about it and this eliminates confusion or controversy. That's what's meant by context. Respect the past, but create something new and build on it. Use creativity and you will succeed.

So many old-timers who still remember the Mardi Gras have come to the History Project to share their vivid memories and to express their joy at seeing the spirit of the old event continue as the Mermaid Parade. This is amazing considering that the last Coney Mardi Gras parade last took place more than 60 years ago!