"Watch Her Dance to the End of Love," Benny's storefront on West 12th Street. Photo by Charles Denson.

By Charles Denson

A phone call from Benny always began with a private joke: “Charlie, tell me what’s new in the World’s Playground.” A bit of irony. The amusement world that Benny had known all his life was fast disappearing. He was old-school and didn’t follow Coney Island politics or gossip. Our long conversations took place in the off-season, when things were quiet. During the summer Benny worked his games 12 hours a day, seven days a week, and had no time to talk. He stayed focused on his little world on West 12th Street.

After years of trading stories, I asked if he wanted to record an oral history. He said, “When I’m gone you can tell my story.” We recorded over several years. No one else could better express the ups and downs, the joy and despair of working and living in Coney Island. He had many lives, a survivor in a sometimes cruel world. You can listen to Benny Harrison's oral history here: https://www.coneyislandhistory.org/oral-history-archive/benny-harrison

Benny was a quiet, well-read contrarian: shy, elusive, creative, brilliant, a sweetheart who was difficult to pin down and always absorbed in a heavy book about world history, architecture, or philosophy. He liked silly jokes and puns and spoke in riddles. He was a quiet genius always inventing, building, restoring, or repairing mechanical devices in his cramped, tiny shop behind the games. He enjoyed making people smile by providing unusual tableaus, signs, displays, prizes, toys and tricks, things like the dancing marionettes that no one else offered. Objects remembered from childhood.

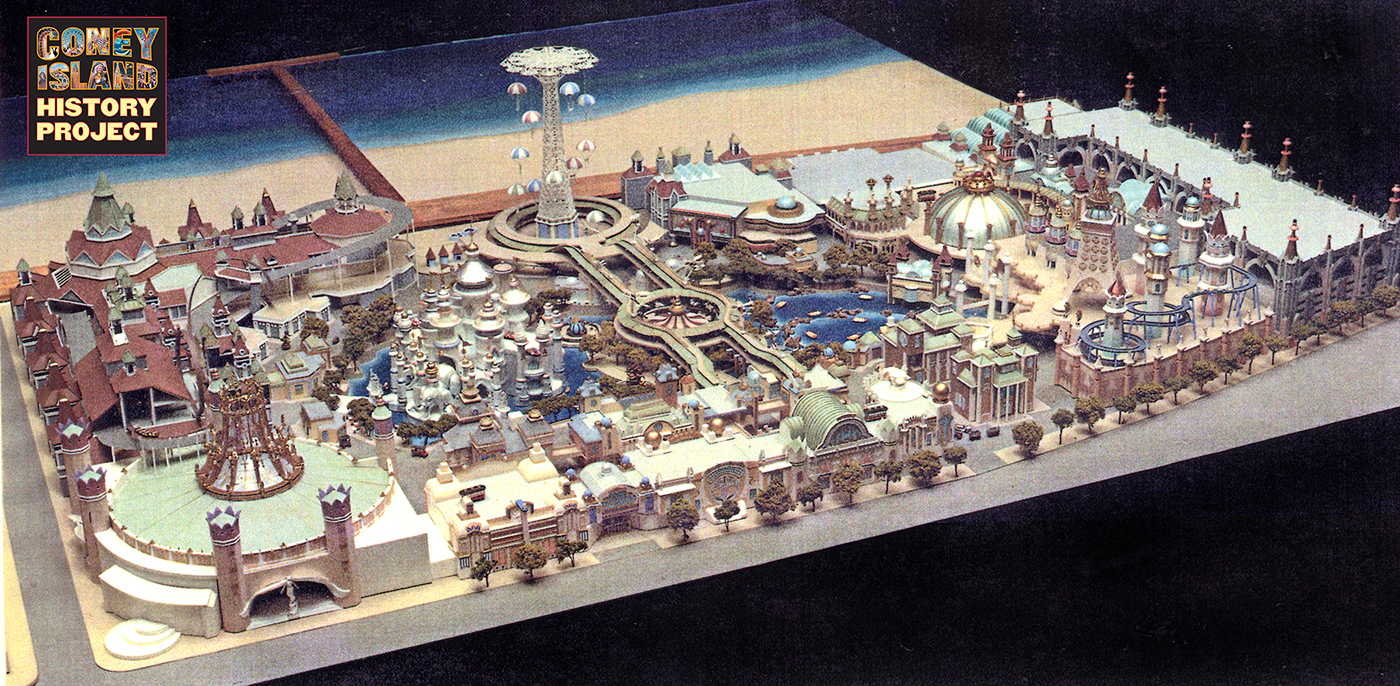

In 2011 the Coney Island History Project moved to Deno’s Wonder Wheel Park and the following year Benny left Jones Walk when the Vourderis family gave him the space next door to ours. We became twin attractions on 12th Street! His stand was bright and colorful. Next to his Skin-the-Wire game were two of Benny’s idiosyncratic creations: the mechanical Dancing Girl (Miss Coney Island) and the adjacent animated Coney Island diorama portraying a happy miniature world.

The Dancing Girl danced to unusual tunes chosen by Benny: sometimes reggae but usually the Australian bush ballad “Waltzing Matilda” or the sentimental version of “Over the Rainbow,” by Hawaiian singer Israel Kamakawiwoʻolei. Both attractions can still be played for a quarter, something unheard of in Coney Island. A small sign says that you can "fall in love" for 25 cents. He later added the cute mechanical kitten and puppy that dance and wiggle below Miss Coney Island’s feet. The Dancing Girl has thousands of friends who come to visit and dance with her each summer.

The signs above Benny’s games are often a source of bewilderment: “Watch Her Dance to the End of Love” a reference to the Leonard Cohen song, “Dance Me to the End of Love.” “Coney Island Always” is the optimistic sign that hangs above a lively miniature animated Coney Island window display. And of course, “Don’t Postpone Joy.”

In his final years Benny still came to work while recovering from cancer, heart disease, and a series of strokes. Benny never took the simple path. He was still building, repairing, and restoring his own games while also helping solve mechanical problems for others. Some of his games were overly complicated puzzles. He’d sit back and watch customers try to figure them out. The games were fun, but not big moneymakers, and sometimes it seemed that he was building them just to amuse himself.

Benny had a hard life. He grew up in Coney Island during the 1940s and 50s, and at the age of 12 began working in his father’s candy factory. His father died young. He was a gambler who lost the family business in a card game, plunging the family into poverty. Benny and his mother wound up living in a one-room apartment in Sea Gate while trying to pay off his father’s debts.

Benny continued in the candy business as a teenager with a stand at Feltmans Restaurant that he and his mother operated. When Feltmans closed, they became Astroland’s first tenant. During the park’s construction, Benny had two cotton candy machines on a plywood box, painted red and white, powered by an extension cord reaching from a nearby restaurant. Business was conducted over the fence.

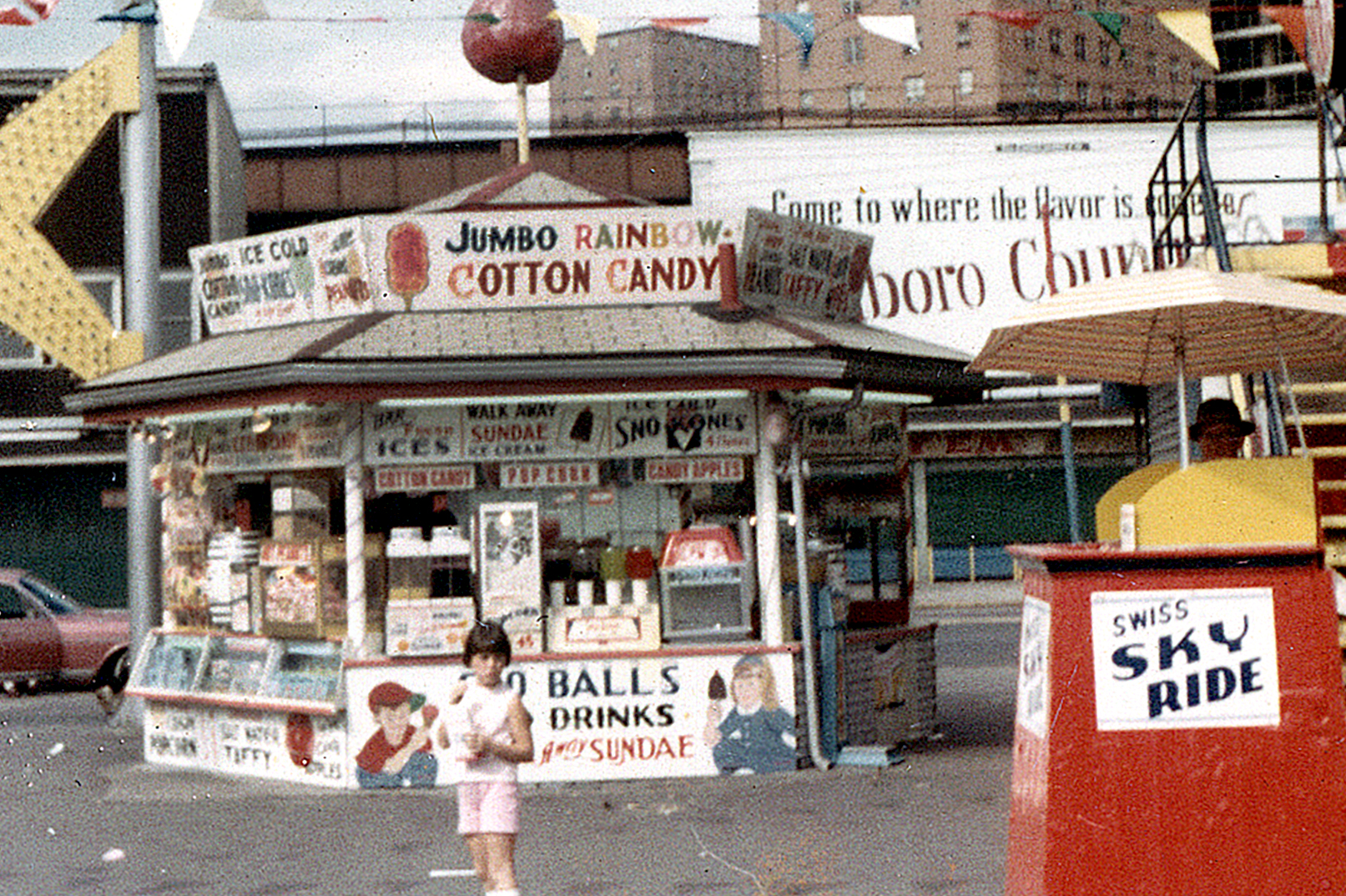

Benny's hexagonal stand in Astroland, c. 1963. Photo © Coney Island History Project

In 1963 Benny hired an architect and commissioned a new stand, a hexagonal structure just inside the entrance to the park. Benny worked at the new store while studying engineering at Hunter College night school, where he had enrolled at age 17. The following year he was drafted into the Army.

Benny hated the Army and took an exam for Naval Aviation at Floyd Bennett Field and received high scores. The draft board sent him to the Navy Aviation Electrical School in Jacksonville, Florida, for training in building jet plane control systems. This is where he learned the skill for building animated figures and robotics. He learned to build games by working on military fighter jets. Benny remained in the Navy reserves for six years while working in Coney Island and expanding his numerous businesses.

During the 1960s Benny began buying up Coney Island property. After Astroland expanded, he was forced to demolish his hexagonal stand, but opened two soft ice cream stores in the park. He purchased several distressed properties, including the old Shore Hotel on Henderson Walk at Surf Avenue. On the day that the sale closed on the hotel, the FBI stopped Benny from entering the building as they were arresting a fugitive from their 10 Most Wanted list who was living upstairs in the hotel. A week later the hotel manager had a stroke, and Benny found himself running a hotel. From there it went downhill.

Benny bought and later lost the Shore Hotel on Surf Avenue in the 1960s. It was demolished in 2011. Photo by Charles Denson.

Next, he bought a one-story structure next to the Popper Building (now a shooting gallery) and opened a colorful storefront selling candy apples, popcorn, frozen bananas, ices, and taffy. Benny developed new candy products such as a caramel coconut popcorn that became quite famous. He used antique machines with heavy brass molds to produce all kinds of sweets.

Benny's candy store on Surf Avenue in the late 1960s. Photo © Coney Island History Project.

Benny operated successful businesses at both locations only to lose the buildings and businesses due to a failed marriage and brutal divorce. Later, the owners of these properties would make millions by selling them during the Coney Island rezoning.

Benny started over with a variety of games. He teamed up with game builder Charlie Walker and opened a small machine shop. He also ran a printing business and traveled to flea markets and fairs selling lithographs and toys. He built penny pitches, fishing games, shooting galleries, boxing puppets, carnival wheels (one of which wound up in the movie Goodfellas), and every kind of game imaginable, all with a twist, a Benny signature of sorts that made them unique.

Coney Island became violent in the 1970s, and it was risky to operate open games. Ride booths were attacked, and buildings were vandalized, burned, and burglarized. The Homicides street gang broke into Benny’s Boardwalk store and stole most of his equipment. He also lost several dozen antique mutoscope arcade machines that were in storage, machines that now sell for thousands of dollars each.

Benny in his shop repairing an antique arcade machine from the 1920s. Photo by Charles Denson.

Eventually Benny wound up on Jones Walk, in a stand that Jack Ward owned. His neighbors were his sister and brother-in-law, Dinah and Wally Roberts. Wally owned the historic Grashorn Building on the Walk and gave Benny a space upstairs to use as a shop. Jones Walk was alive and thriving with all kinds of games until the rezoning of Coney Island in 2009, when all the properties changed hands. Jones Walk would never be the same, and the future became bleak for the small independent businesses that once operated there.

Benny would have gone out of business if it weren’t for the kindness of the Vourderis family, owners of Deno’s Wonder Wheel Park. He reopened his games and a small shop in the space below the kiddie park. The store was soon filled with prizes including marionettes, jewel boxes, and a million toys. Everyone who played the games got a prize, win or lose. Benny was able to enjoy another decade of intrigue in the heart of the World’s Playground.

Benny Harrison died on March 11, 2024. He was cared for and looked after by his friends who worked with him and loved him and put up with his nonsense. With his passing went a way of life that is slowly coming to an end. Benji, you will be missed.

You can listen to Benny Harrison's oral history here: https://www.coneyislandhistory.org/oral-history-archive/benny-harrison

Benny contemplates the crowd at his stand during the Mermaid Parade. "They don't play the games," he lamented, "they only drink!" Photo by Charles Denson

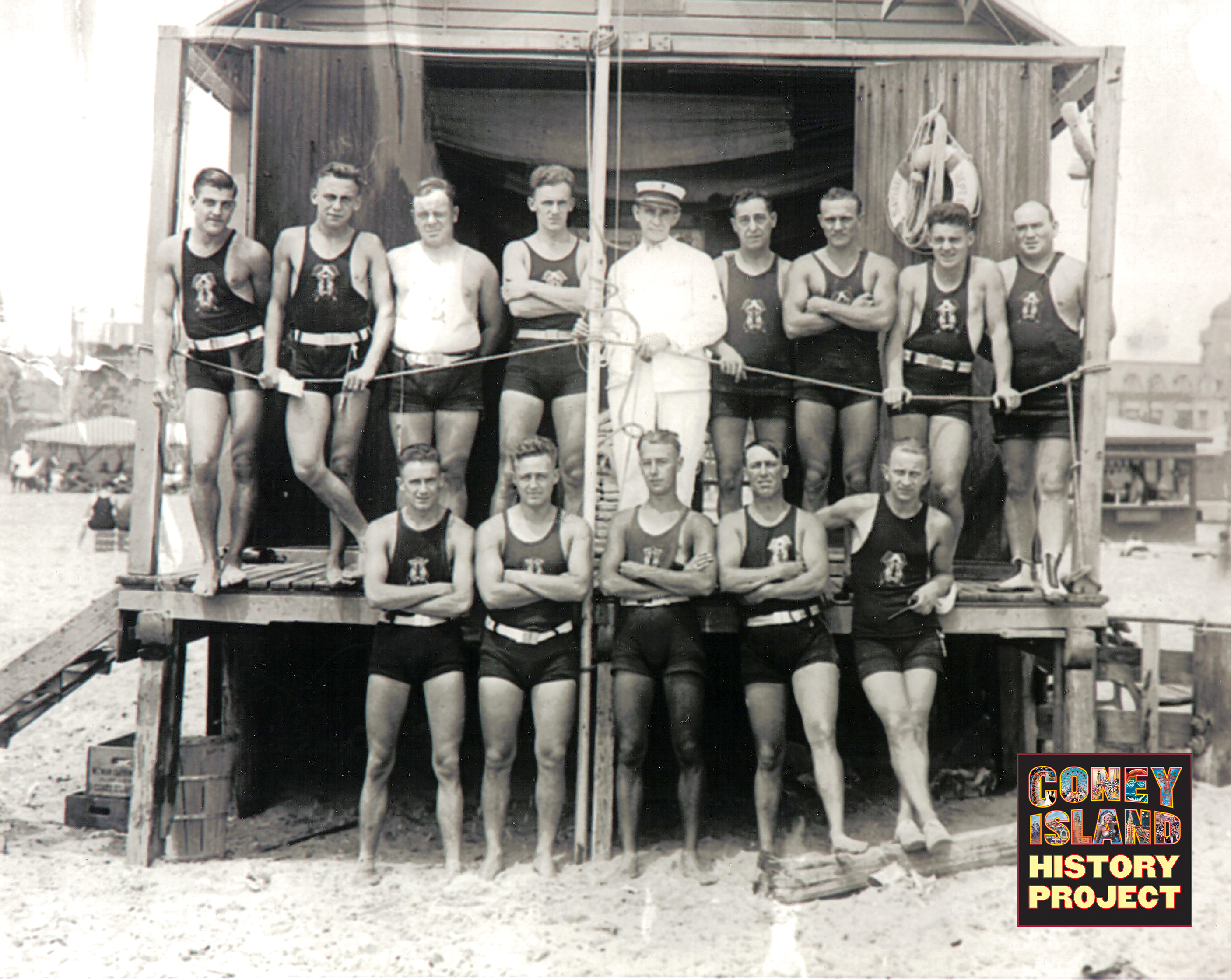

U.S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps lifeguards at their headquarters on the beach at West Fifth Street, Coney Island, c.1919.

U.S. Volunteer Life Saving Corps lifeguards at their headquarters on the beach at West Fifth Street, Coney Island, c.1919.

Volunteer lifeguards on the Coney Island Beach, 1920. Ernest Gross is second from right. (Dog at center was not a lifeguard.) The Municipal Bathhouse can be seen behind them.

Volunteer lifeguards on the Coney Island Beach, 1920. Ernest Gross is second from right. (Dog at center was not a lifeguard.) The Municipal Bathhouse can be seen behind them.  Lifeguards at the Coney Island boathouse.

Lifeguards at the Coney Island boathouse.