The Coney Island History Project will celebrate Coney Island’s 200th birthday on October 28th by displaying and honoring Coney Island’s oldest surviving artifact: the 200-year-old Coney Island Toll House sign that dates to 1823. Please join us! Our exhibition center at 3059 West 12th Street next to the entrance to Deno’s Wonder Wheel Park will be open on Saturday, October 28, from 1 PM – 5 PM. The rain date is Sunday, October 29. Admission is free of charge.

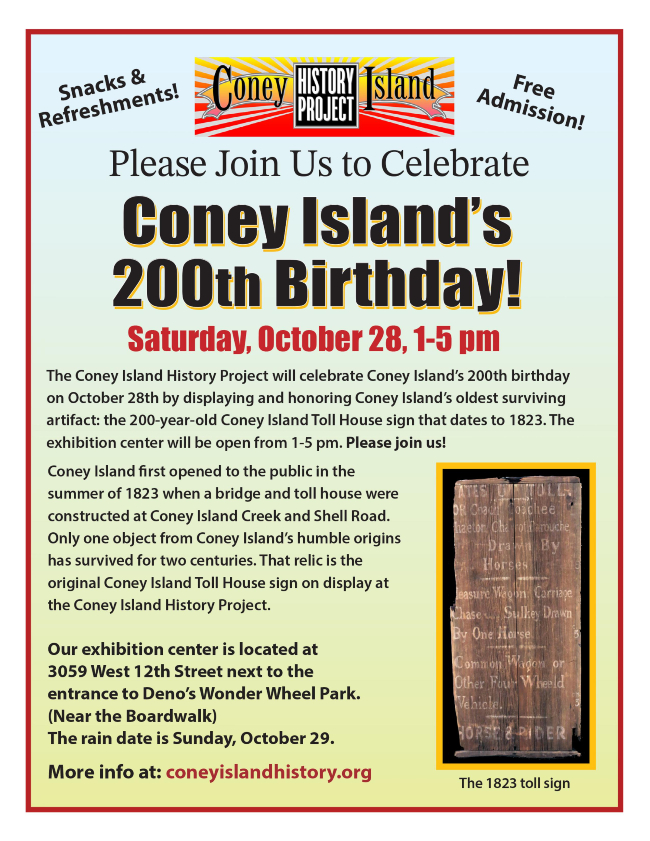

Coney Island first opened to the public in the summer of 1823 when a bridge and toll house were constructed at Coney Island Creek and Shell Road. Only one object from Coney Island’s humble origins has survived for two centuries. That relic is the original Coney Island Toll House sign on display at the Coney Island History Project. And for that we thank Carol Albert, co-founder of the Coney Island History Project, who rescued the sign and had it restored.

In his film shared above and the following essay, History Project director Charles Denson tells the story of “Coney Island’s Oldest Artifact: How the Coney Island Toll House Sign Survived for 200 Years.”

Coney Island first opened to the public in the summer of 1823. A one-paragraph article buried in the August 18, 1823, New York American breezily announced the opening: “The Road and Bridge leading to this delightful island are now complete. It is open the ocean, with the finest and most regular beach we ever saw . . .” From these humble beginnings Coney Island would soon become the most famous resort in the world.

Until 1823 there was no public access to the island. Coney Island began as “common land” shared by 39 property owners in the village of Gravesend. The island was a pristine environment known for mountainous sand dunes, a vibrant salt marsh, the sparkling beach, juniper forests, and cool ocean breezes. Coney Island Creek was a popular spot for fishing and hunting waterfowl, but before the Shell Road bridge was built, the island could only be accessed by rowboat. The Island’s only resident was Abram Van Sicklen, whose small farm was located on the creek.

In March of 1823 Gravesend formed the Coney Island Road and Bridge Company in order to provide better access to the island. Shell Road was extended one mile through a vast salt marsh to the new bridge. A wooden toll house and gate were constructed on the banks of Coney Island Creek. Gravesend resident James Cropsey was appointed to operate the Road and Bridge Company. In the first days after the road opened, toll-taker Daniel Morell counted 300 horse-drawn vehicles crossing the bridge.

A simple sign at the toll gate listed the fees to enter the island. These ranged from 5 cents for a “horse and rider” to 50 cents for a “coach drawn by horses.” The sign also listed the “Rate of Toll” for a “Coach, Carriage, Pleasure Wagon, or Sulkey.” In 1829 a wood-frame hotel opened near the toll house. Others hotels and roadhouses soon sprang up around it. By the 1830s, Coney Island had become a popular destination.

The entrance to Coney Island was picturesque, with a canopy of weeping willows shading the toll house, and verdant Coney Island Creek beside it. John Lefferts operated the bridge and tollhouse from the 1830s until 1876, when Andrew Culver bought the property for his railroad. Tolls were no longer collected and the toll house was transformed into a private residence. Culver’s Prospect Park & Coney Island Railroad was later consolidated into the New York City transit system. The F-train now follows its former route.

The toll house fell on hard times. The wooden toll sign, a curiosity from earlier times, remained attached to the toll house. The neglected creek-side structure was forgotten as it fell into disrepair. In 1929 the century-old historic building was finally demolished when Shell Road was widened and realigned. The toll sign was the only thing that was saved.

The sign’s remarkable history and provenance after the toll house was razed can be accurately traced. In 1928 the sign was removed from the toll house by ride manufacturer William Mangels Jr. and displayed in his father’s amusement museum, located one block away on West 8th Street.

The museum soon closed for lack of interest, and most of its artifacts were sold off. The sign remained at the factory. In 1964, six years after William Mangels Sr. died, his son sold the sign to folk-art collector Frederick Fried, who was also buying up hundreds of artifacts from Steeplechase Park following the park’s closure. Fried stored his vast Coney Island collection in a barn in Vermont but kept the sign displayed on the wall of his apartment on Riverside Drive. This turned out to be fortunate for the sign. In the early 1980s, the Vermont barn burned to the ground, and Fried’s entire collection of historic Coney Island artifacts went up in flames. Fred Fried died shortly afterward.

Fried’s estate sold the toll house sign to Nick Zervos, who kept it in his private collection. It was not seen again for decades. In 2003 I was contacted by Brooklyn antique dealer Charlie Shapiro who was a fan of my Coney Island book. He told me he had an important artifact he was selling, and asked if I was interested. He said that Nick Zervos had passed away, and his family was selling the Coney Island Toll House sign. The historic sign had finally resurfaced! I told him that I was VERY interested.

I agreed to meet Shapiro at his apartment. After small talk, we entered his kitchen and he pulled the sign out from a narrow space between his kitchen sink and the refrigerator. It was not in good shape. I asked the price and realized that it was beyond my finances but the sign had to be saved. I hated the thought of this historic object being sold into another private collection, never to be seen again.

Soon after finding the sign, I met with Carol Albert, owner of Astroland. We were in the early days of forming the Coney Island History Project. I told Carol about the historic sign that was stuck in a dank space next to a kitchen sink and was about to be sold off. What was truly amazing is that the sign was accompanied by detailed documentation showing its removal from the toll house in 1928. Carol asked me briefly about Shapiro. I thought that was the end of the story.

Later in the week Carol told me she had something to show me. I entered her office, and there was the sign, leaning against the wall. Carol had rescued it and said that the Albert Family was donating it to the History Project.

The fragile sign was in a deteriorated state and needed professional restoration before returning to Coney Island. The wood was severely rotted, crumbling, and insect damaged. The sign was in such poor condition that it could not be safely handled or displayed. Carol arranged for a professional restoration, which included new backing, thermoplastic resin injected into the damaged wood, and highlighting the faded lettering with a reversible transparent wash. Ultraviolet light and infrared photography revealed no hidden lettering.

Following the restoration the Toll House Sign was put on display at the History Project, just a few blocks from where it first greeted travelers 200 years ago. The sign’s importance is symbolic. It represents the endurance, continuity, and resiliency of Coney Island. It is the only object that was there at the beginning, the only link to the origins of the World’s Playground.