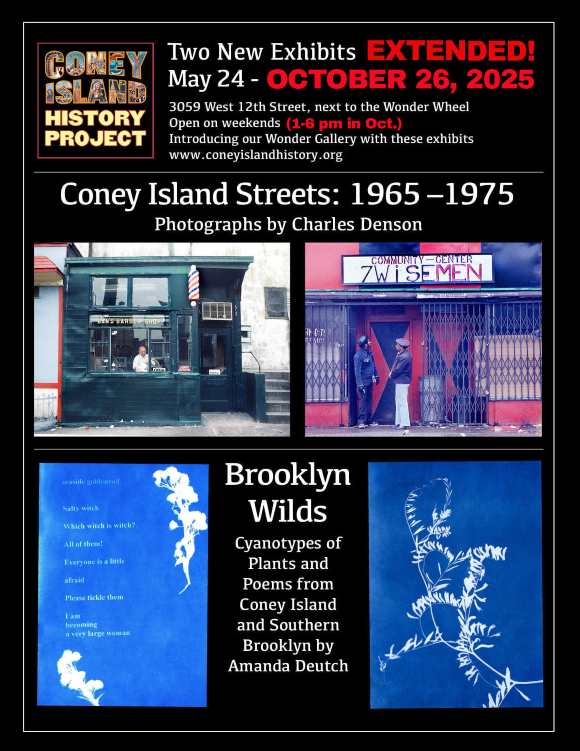

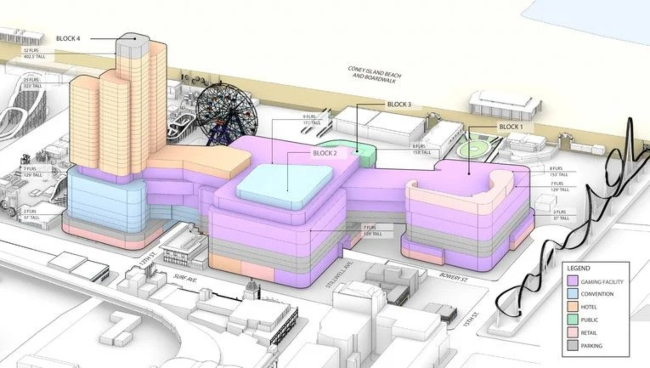

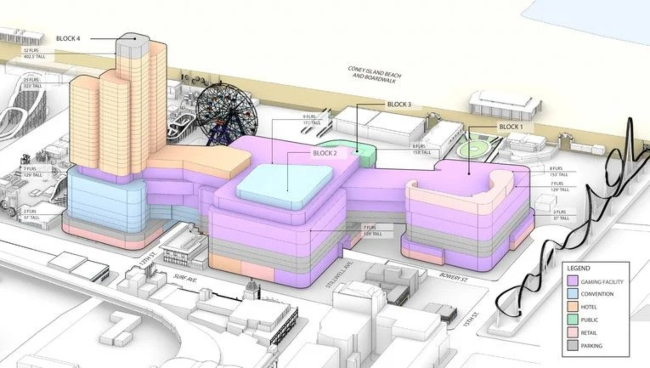

Developer's rendering of the massive casino proposed for Coney Island.

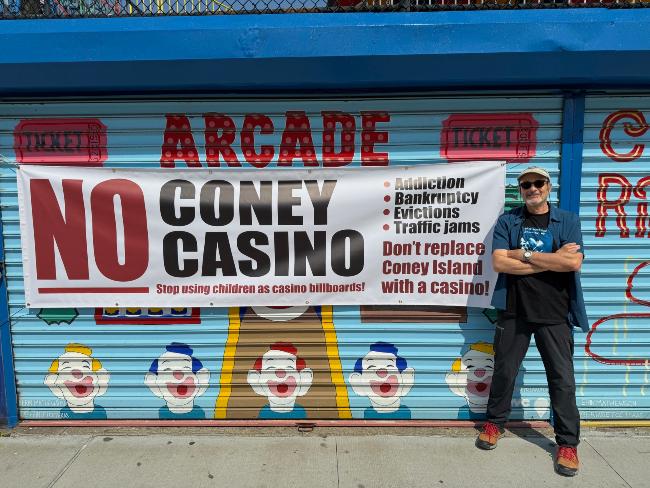

Do you live, work and/or play in Coney Island? Community Board 13 hearings, including this Wednesday, January 22, are the first of many crucial hearings and votes on the Coney casino project. “The project’s Environmental Impact Statement reveals an out of scale monstrosity that will choke off and smother all surrounding business and destroy the fabric of the surrounding community,” said Charles Denson, Executive Director, Coney Island History Project, at last week’s Land Use Committee hearing. Scroll down this page to read the rest of his comments or watch on YouTube at 1:25.

Your presence at public hearings and your letters and calls to officials who will vote on the casino in the coming weeks and months are essential. The upcoming hearings are about the developer's proposal to de-map public streets and acquire air rights to build sky bridges and a 400-foot-tall hotel, which is twice the height allowed by existing zoning. The process to award the casino license is expected to come by the end of this year.

In 2023 and 2024, the developer paid registered lobbyists over $400,000 to lobby elected and appointed officials and their staffs, including Coney Island Council Member Justin Brannan, Brooklyn Borough President Antonio Reynoso, City Planning Commissioners, Office of the Mayor, Deputy Mayors, and Economic Development Corporation. (TSG Coney Island Entertainment Holdco LLC via lobbyistsearch.nyc.gov.)

Let your voices be heard by writing or phoning these elected and appointed officials and by signing and sharing the petition against the Coney Island casino organized by our friend and neighbor Coney Island USA. Over 6,000 people have signed the petition since December, with dozens more signing every time it is shared via social media.

The timeline of upcoming hearings, reviews and votes on the de-mapping proposal is as follows. (You can view the timeline in progress on City Planning's Zoning Application Portal at https://zap.planning.nyc.gov/projects/2024K0230):

Community Board Hearing

January 22, Wednesday, 7 PM, Community Board 13 Hearing at South Brooklyn Health (Coney Island Hospital), 2601 Ocean Parkway, 2nd floor auditorium. In-person meeting only.

-You must sign up to speak (two-minute maximum) by emailing hglikman@cb.nyc.gov no later than Tuesday, January 21 at 2 PM.

-Following the CB 13 Land Use Committee’s “No” vote on January 15, the full community board voted "NO" on the proposal.

Draft Environmental Impact Statement Public Hearing

-Date TBA. Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) must be completed ten days prior to the City Planning Commission vote.

Borough President Review

-The Borough President had 30 days after the Community Board issues a recommendation to review the application and issue a recommendation. A public hearing was held on March 10 and thr borough President issued a conditional approval of the land use proposal: https://www.cbsnews.com/newyork/news/coney-island-amusement-park-casino-proposal/

-Write or phone Antonio Reynoso, Brooklyn Borough President. 718 802-3700. AskReynoso@brooklynbp.nyc.gov. Mail: 209 Joralemon Street Brooklyn, NY 11201.

City Planning Commission Review

-The City Planning Commission held a public hearing on the DEIS (Draft Environmental Impact Statement) on March 19. CPC has 60 days after the Borough President issues a recommendation to hold a hearing and vote on an application.

-How to participate: https://www.nyc.gov/site/planning/about/commission-meetings.page

-Email your comments to 24DCP129K_DL@planning.nyc.gov. Deadline for comments is March 31 at 5 PM.

City Council Review

-The City Council has 50 days from receiving the City Planning Commission report to call up the application, hold a hearing and vote on the application.

-Council Member Brannan’s vote is extremely important because it’s customary for NYC Council members to vote with the local council member. Justin Brannan is term limited and currently running for citywide office as NYC Comptroller.

-Write or phone Justin Brannan, Councilman for the 47th District (Bay Ridge, Coney Island, Sea Gate and parts of Dyker Heights, Bath Beach and Gravesend). 718 748-5200. AskJB@council.nyc.gov. Mail: District Office, 8203 3rd Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11209.

Mayoral Review

-The Mayor has five days to review the City Council’s decision and issue a veto.

Applicants must complete this local land-use/zoning process in order to be eligible for consideration by the New York Gaming Facility Location Board, which is overseeing the commercial casino siting process in the Metro New York region. Casino applications will be due June 27, 2025.

Statement by Charles Denson, Executive Director of the Coney Island History Project at Community Board 13 Land Use Committee Hearing on January 15, 2025

I am asking the community board to reject the de-mapping of streets for the Coney casino project.

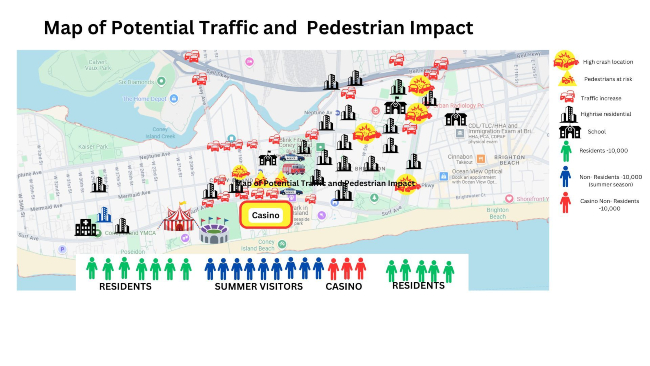

The project’s Environmental Impact Statement reveals an out of scale monstrosity that will choke off and smother all surrounding business and destroy the fabric of the surrounding community.

De-mapping of public streets is not needed to build this project. The zoning permits them to build as of right. The developers are asking for the streets to be de-mapped so that they can buy air rights to build sky bridges connecting all the Thor Equities properties. The purpose of a sky bridge is to make sure that no one leaves the casino once they enter it. They want to cut people off from all surrounding streets and attractions and keep them inside gambling until their money runs out. The casino has a business plan based on gambling addiction.

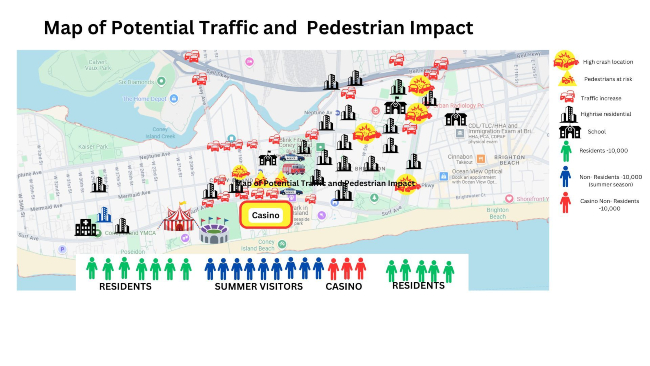

The developers are asking to transform Stillwell Avenue into a pedestrian mall that will funnel people into the casino. Transforming Stillwell Avenue will severely limit emergency access to the beach, Boardwalk, and amusements for nearly a quarter-mile stretch of the world’s most crowded beachfront.

The developers also want to transform West 12th Street into a four lane driveway for the casino. The project’s environmental impact statement confirms that this will create a choke point and traffic nightmare at this intersection and all along Surf Avenue. De-mapping of streets will disrupt historic family-oriented businesses of Coney Island. This land grab benefits no one but greedy developers.

There is also no guarantee that this project will be viable or sustainable once the novelty wears off. It could wind up abandoned like the Shore Theater. The proposed casino is a dead whale on the shores of Coney Island. Please vote no on the de-mapping.