Charles Denson at the silenced Wonder Wheel, 2020, "a season like no other."

For the first time in history, Coney Island has lost an entire season. As Labor Day weekend arrived and faded, amusements remained shuttered and people began wondering aloud if the neighborhood can recover. The pandemic is testing the will and finances of even the most dedicated businesses and residents. This year was expected to be the greatest of this century, with important anniversaries, exciting events, and new attractions. None of this happened. But Coney Island has been tested before. Pestilence, war, crime, and weather have challenged the island, and each time it has clawed its way back.

Coney had barely begun life as a resort in the early 1800s when its remote location made it a prime candidate for New York's quarantine station. Yellow fever and cholera epidemics had swept through New York, and the city sought to build a massive facility that would house immigrants with infectious diseases for 40 days. Coney was on the short list in the 1850s but it turned out that the location was not remote enough. Instead, the station opened on two smaller islands, Hoffman and Swinburne, built from landfill in the waters just west of Coney Island.

In the 1870s, long before amusement parks arrived, Coney Island became a refuge for poor children suffering from tuberculosis and other diseases. The Coney Island History Project's 2019 exhibit "Salvation by the Sea" documented and highlighted the work of the Children's Aid Societies and the other shorefront summer homes built along the beach. These charitable homes and hospitals, supported by New York's wealthiest residents, became the island's largest landowners and operated until construction of the Boardwalk forced them out. The societies saved thousands of young lives with the "Fresh Air Cure," and trained generations of immigrant mothers in proper hygiene and child rearing that prevented disease in New York's tenements.

Malaria was the culprit at Coney Island in 1903, when disease-carrying mosquitos were found in foul standing water caused by the illegal filling and dumping along Coney Island Creek and the Brighton race track. The entire island was doused and sprayed with noxious oils, from one end to the other, in an attempt eradicate the problem. This created an ugly landscape and did little to solve the problem.

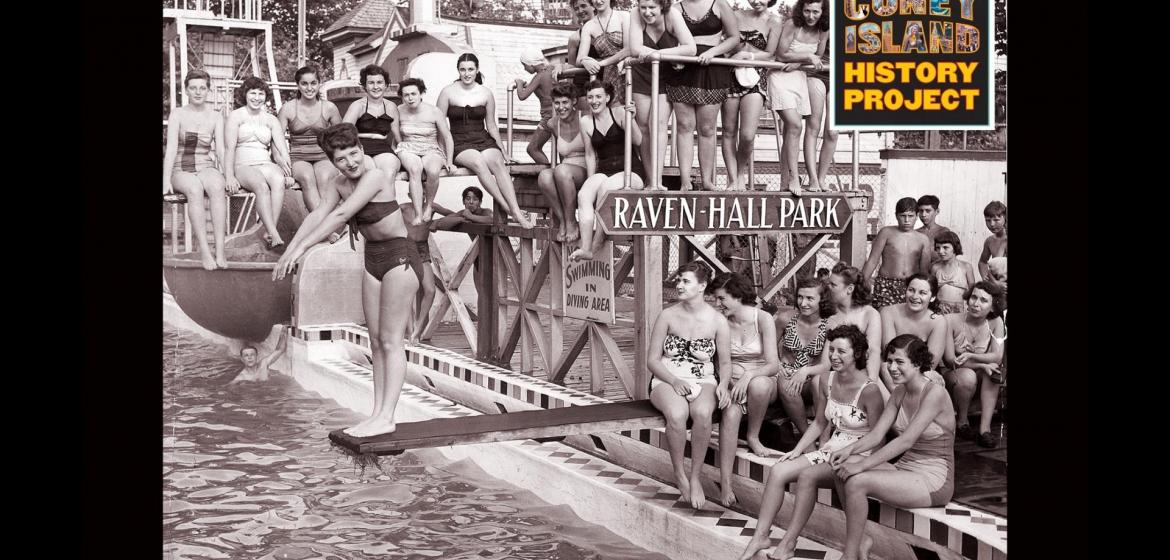

A polio epidemic hit New York hard in 1916, and parents with children were told to avoid amusement parks, swimming pools, and beaches. But the disease was already widespread, and many children suffered the horrifying effects of infantile paralysis before a vaccine was found. Coney Island remained open to the public throughout 1916, but few children were seen at the beach and amusements that year.

The influenza epidemic of 1918 followed the polio epidemic, hitting its peak during the fall and winter of 1919, the off-season, when Coney Island's rides and amusements were already closed and crowds were absent. Coney Island escaped the worst effects of the deadly 1918 flu.

Rationing of oil, metal, and rubber during Word War II made ride maintenance difficult, but Coney Island operators were recyclers and experts at repurposing. Nothing was ever discarded, and the rides continued full blast during the war. The Island's bright lights were "blued out," dimmed, or covered with curtains that faced the ocean side. Luna Park was lit with dim but colorful Japanese lanterns. Coney was considered important for the morale of soldiers on leave, or who were heading overseas and needed a last celebration. The "Underwood Hotel" below the boardwalk was livelier than ever during the war years, filled with romantic couples saying a last goodbye.

Social distancing in Coney Island has a more recent precedent. Street crime was out of control in the mid 1960s, and robbing the exposed ticket booths at rides became the rage for gangs of young thugs. Plexiglas shields and elaborate wire cages soon surrounded all booths and entrances to rides, keeping the public at a distance and protecting operators and patrons from harm.

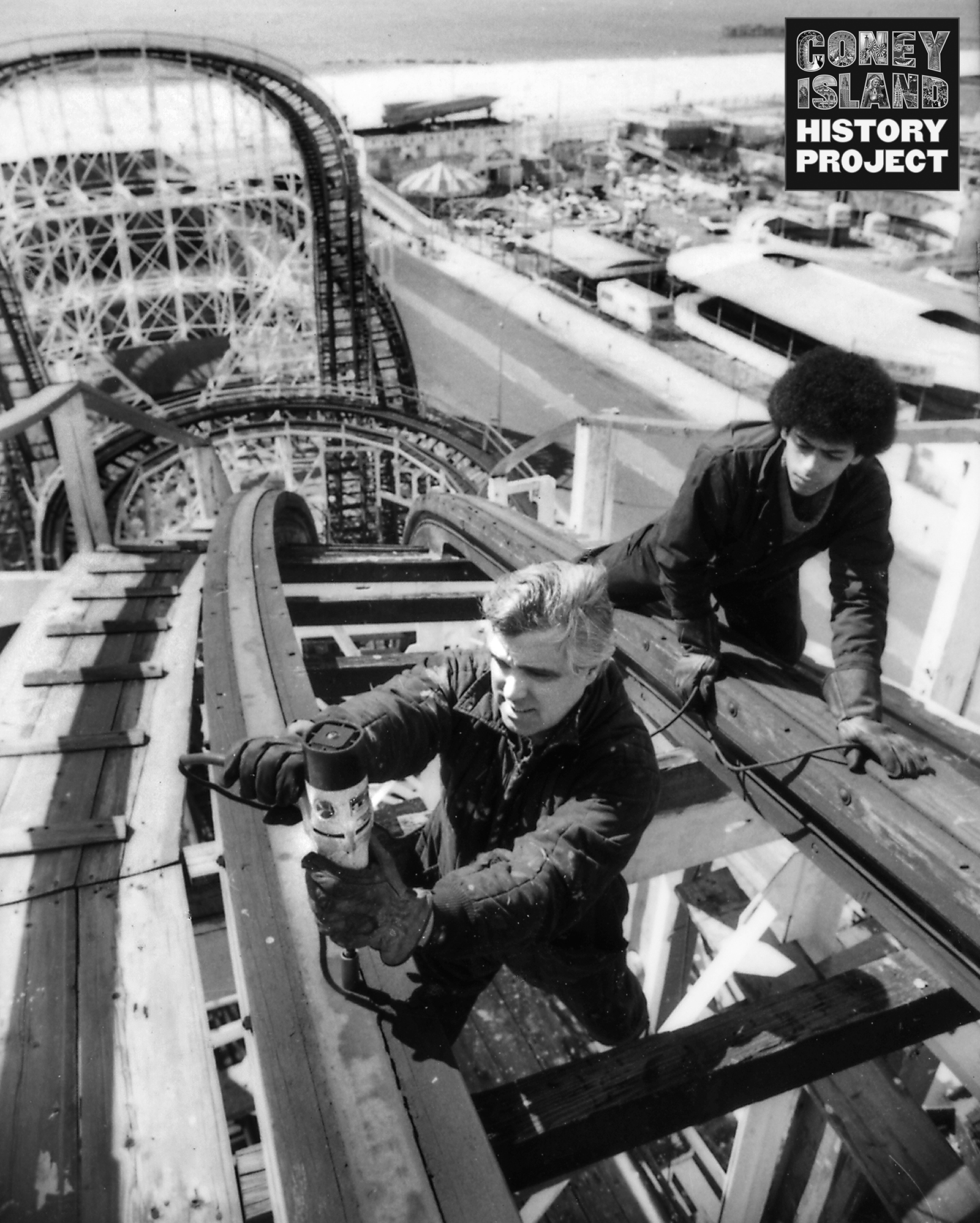

Super Storm Sandy arrived in late 2012 as the season ended. It dealt a devastating blow, but Coney Island's amusements had five months to make repairs before reopening in March 2013. This recovery led to a belief that all obstacles could be overcome.

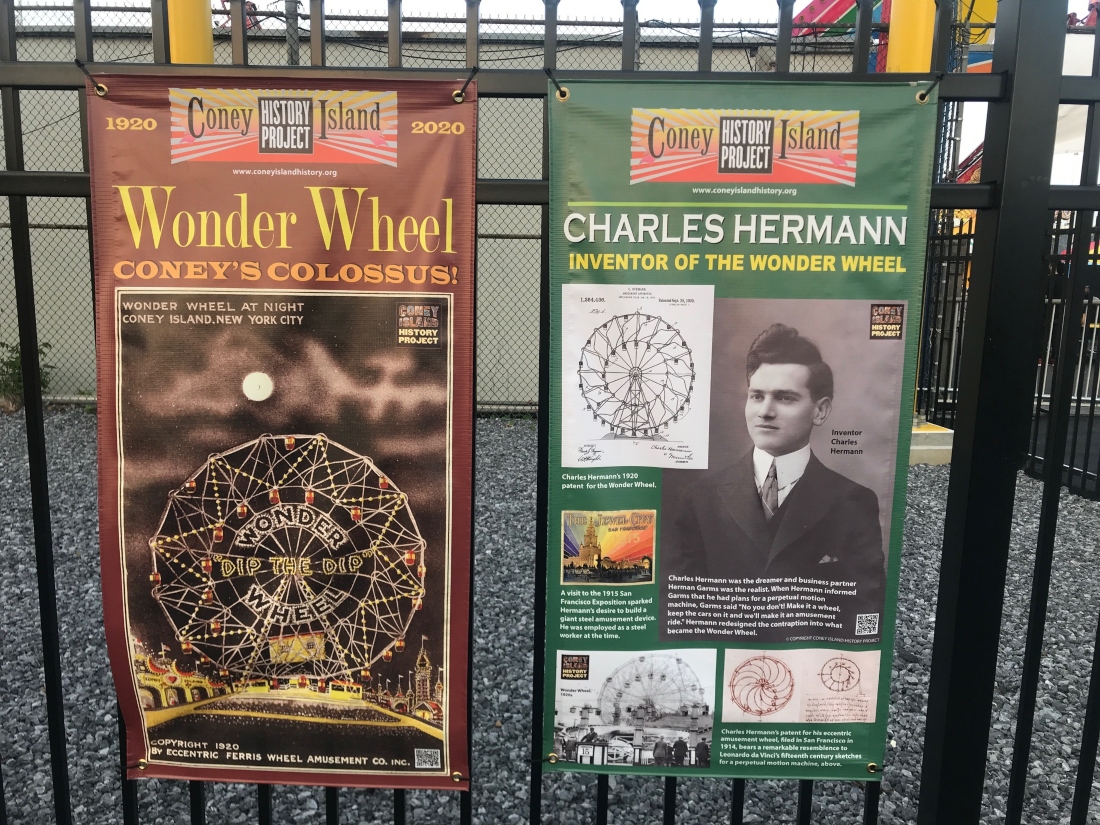

But this year is unlike any other. Coney Island is being tested as never before. The Coney Island History Project and the Vourderis family of the Wonder Wheel had planned to make this centennial season unforgettable, and it turned out that it was, but for reasons that no one could ever have imagined.

Plans for the Centennial celebration of Deno's Wonder Wheel included special events like Broadway musical performers on the park's newly purchased property and our 9th annual Coney Island History Day on the Boardwalk; new and renovated rides, attractions, signage, and murals; and a splendidly refurbished Wonder Wheel. My new book, Coney Island's Wonder Wheel Park, and an accompanying exhibit at the History Project would pay tribute to the history of Coney Island's greatest and oldest continuously operating attraction.

I spent the summer of 2019 researching the history of the Wonder Wheel on a tight publishing deadline so that it would come out in time for Memorial Day. The research was all primary source and I tracked down family members of the Wheel's original designers and operators whose stories had never been told. Many were planning to come to the Memorial Day celebration, including the 95-year-old daughter of Charles Hermann, the Wheel's creator.

The reality of how this season would turn out began to sink in during early spring. "No opening for Palm Sunday? Maybe by Easter Sunday? Delayed until Memorial Day? Of course we'll open by July 4!" The season quietly disintegrated into despair and confusion. A Labor Day Weekend like no other in history came and went.

Due to the pandemic, the Coney Island History Project suspended walking tours, events at schools and senior centers, in-person oral history interviews and the exhibition center season. Starting in March, our staff transitioned to recording oral histories via phone and Skype and creating new virtual programming including podcasts and videos. Our online oral history archive was featured in the NY Times, Time Out NY and Curbed New York as a cure for loneliness, a way to lose yourself in fascinating stories from the past, and visit Coney from afar.

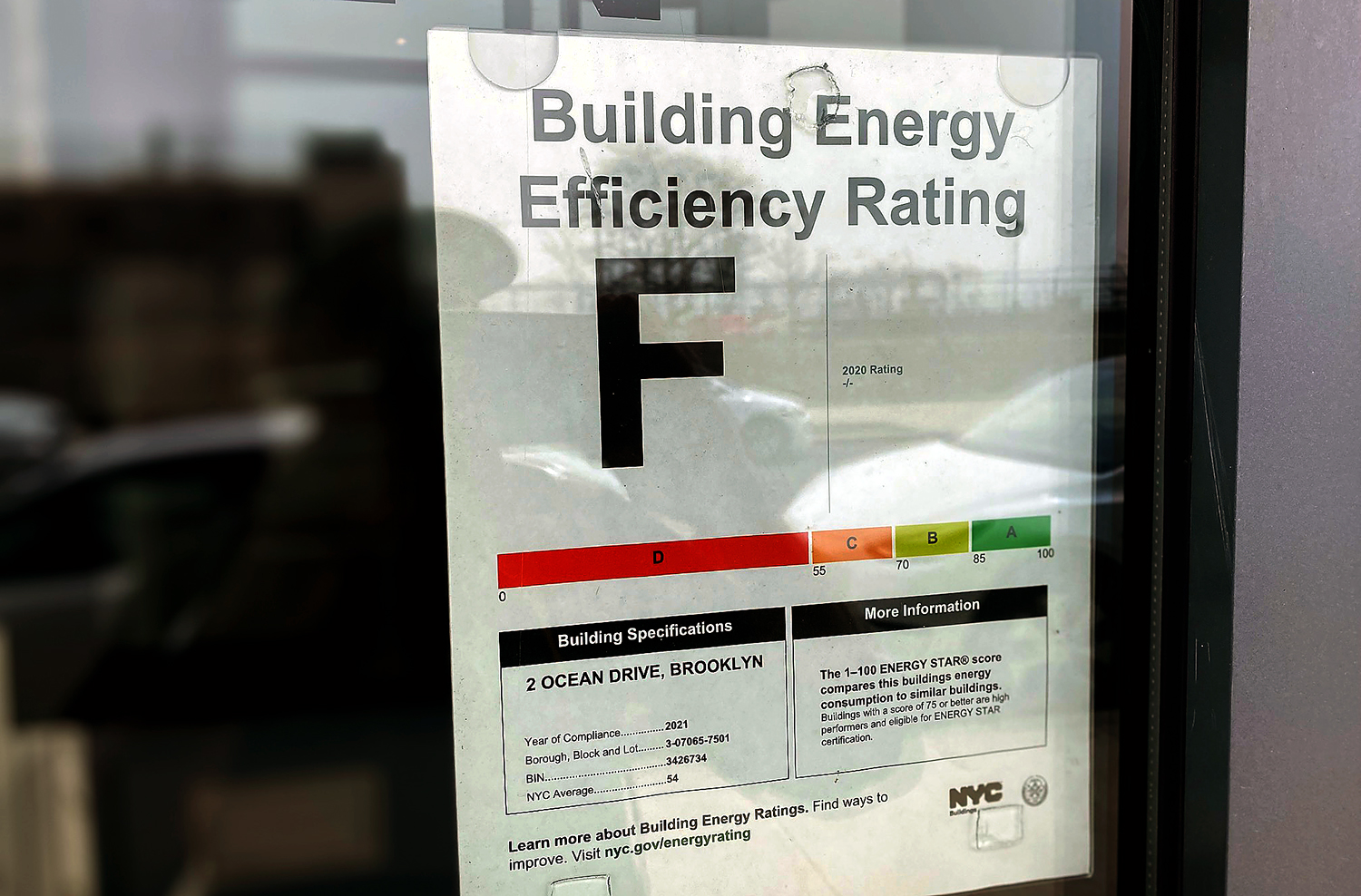

Amusement parks don’t have the option of transitioning to virtual programming but Deno’s Wonder Wheel is an outdoor ride with 24 open-air cars spaced 15 feet apart. It was designed for social distancing and park owners made every effort to provide a safe space for visitors. Masks, Plexiglas, distancing markers, sanitizer stations were all in place, yet the Wheel and the park's other rides remained silent and still due to New York State executive order. And now, as the season comes to a close, we can just hope for a better, safer, and much happier 2021. We will survive.

-- Charles Denson