Happy Holidays and Warm Wishes for the New Year from the Coney Island History Project. We're thrilled to be celebrating our 16th anniversary and Deno's Wonder Wheel's centennial in 2020!

As we look back on 2019, we're grateful to our members, funders, and friends for your continued enthusiasm and support, and proud of all that we've accomplished during the past 15 years. Special thanks to Carol Albert, who co-founded the Coney Island History Project with Jerome Albert in honor of Dewey Albert, creator of Astroland Park, for her ongoing support, and to the Vourderis family, operators of Deno's Wonder Wheel Park, for providing us a home and for their interest in preserving Coney Island's heritage.

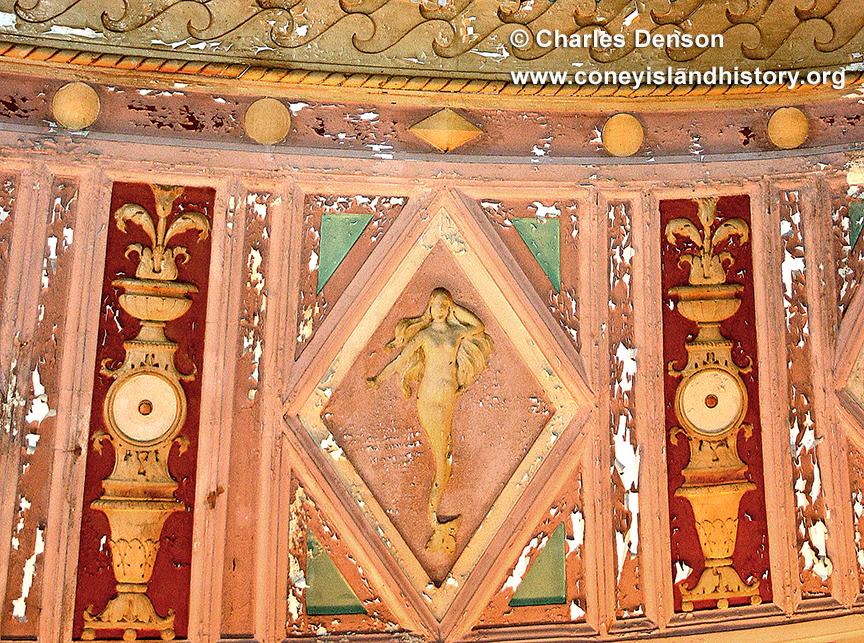

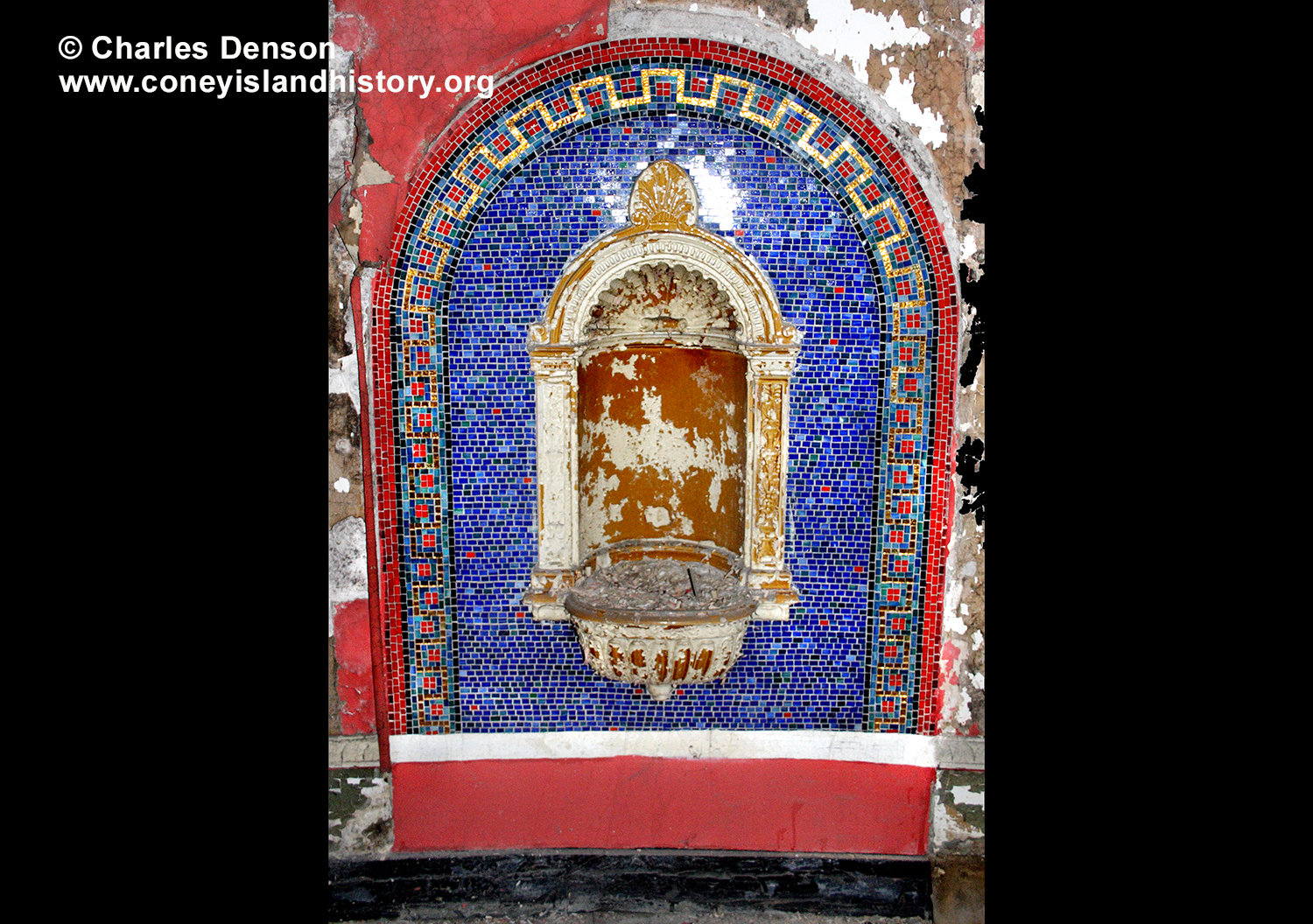

Highlights of our 2019 season include the special exhibition "Salvation by the Sea: Coney Island's 19th Century Fresh Air Cure and Immigrant Aid Societies," which was featured in the Brooklyn Eagle and on WNYC's All Of It. Visitors from the NYC metro area, across the country and around the world took part in themed history weekends at our free exhibition center and snapped souvenir selfies with the iconic Spook-A-Rama Cyclops and Coney Island's only original Steeplechase horse.

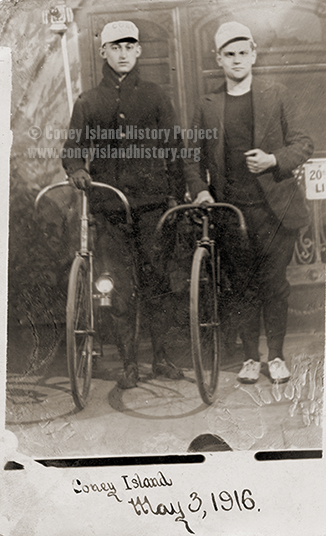

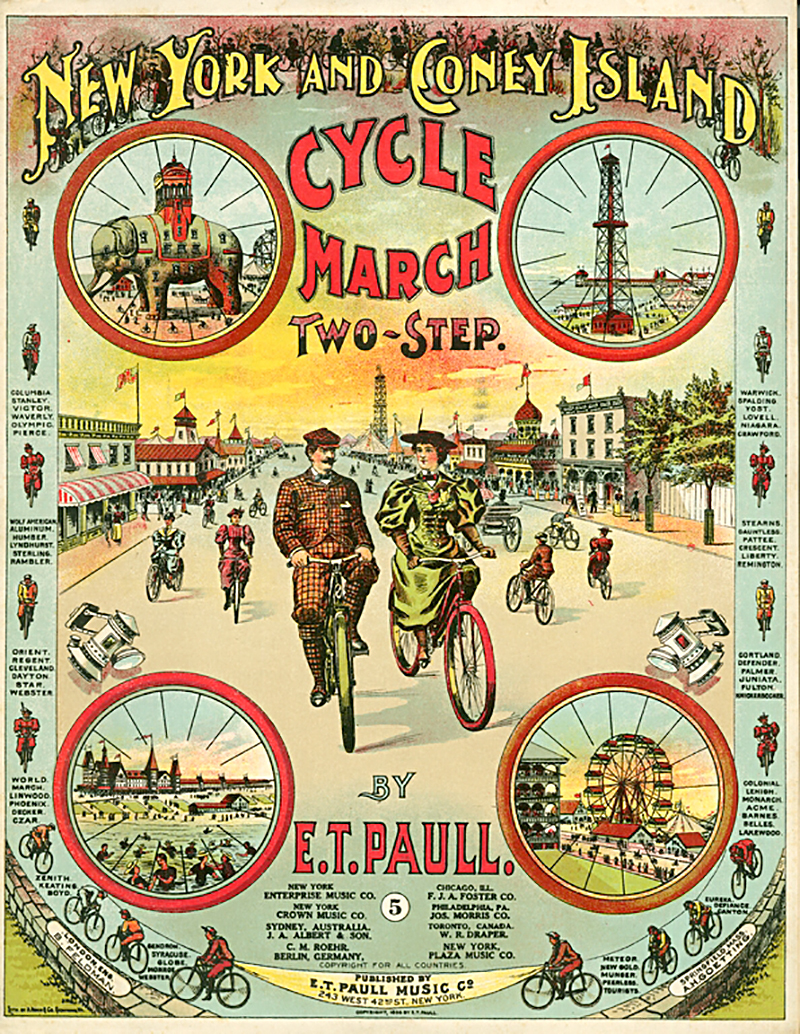

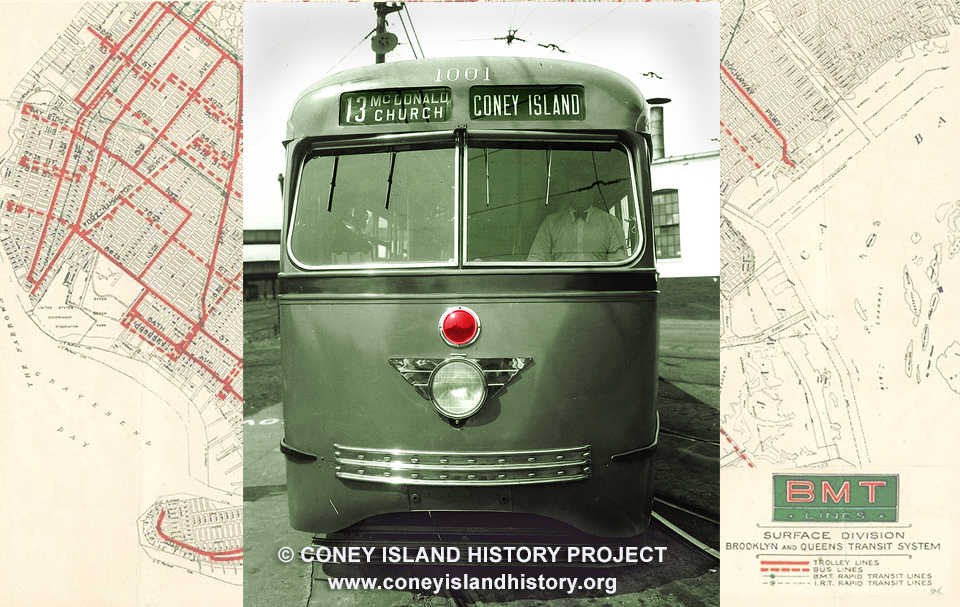

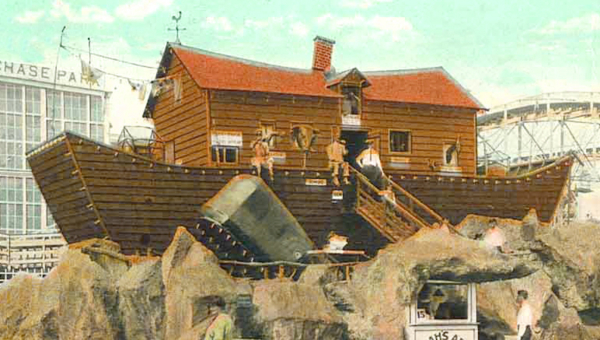

When immigrants sailed into New York Harbor at the turn of the last century, the first thing they saw wasn't the Statue of Liberty, it was the towers and bright lights of Coney Island. Our 8th Annual Coney Island History Day presented with Deno's Wonder Wheel Park celebrated Coney Island's immigrant heritage with performances of Russian classical ballet and Ukrainian folk dance, Afro Haitian drumming, Chinese traditional dance, songs in the Turkish and Rumeli tradition, and a Mariachi band. You can watch a video recap of Coney Island History Day here.

In 2019, we recorded over 50 oral histories in English, Russian, Mandarin, Cantonese and Spanish with people who have lived, worked or played in Coney Island and adjacent neighborhoods of Southern Brooklyn. More than 350 oral histories are available for listening in our online archive and at our exhibition center via our new SoundStik audio handset.

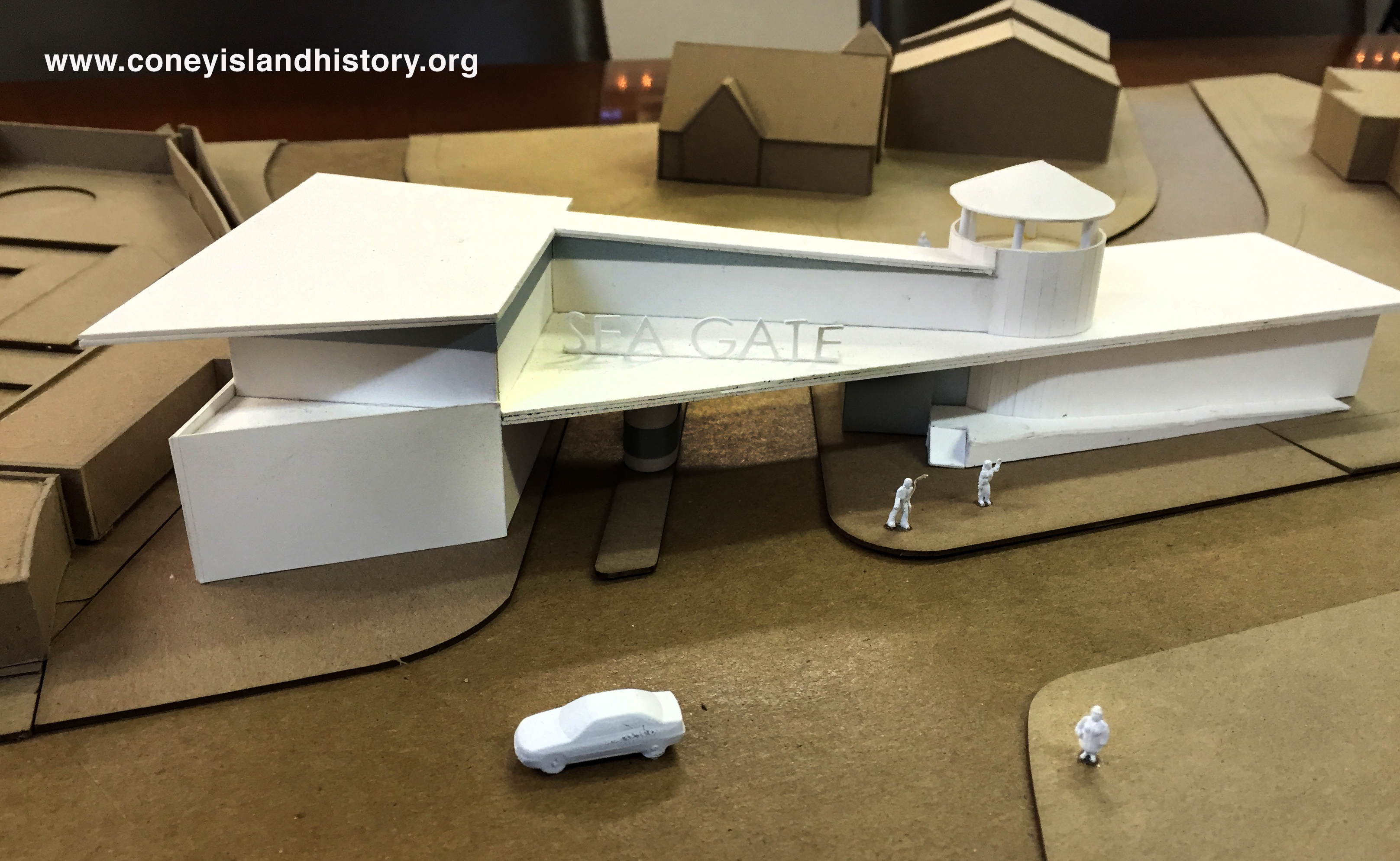

Our free Immigrant Heritage Walking Tour of Coney Island was conducted in English and Mandarin for Immigrant Heritage Week, organized by the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs, and for Jane's Walk, organized by the Municipal Art Society. The Coney Island History Project exhibited at City of Water Day in Kaiser Park sponsored by the Coney Island Beautification Project and the Waterfront Alliance and did presentations about Coney Island Creek at Rachel Carson High School for Coastal Studies and the City Parks Foundation's Coastal Classroom.

Your donation or membership today will help support our 501(c)(3) nonprofit's free exhibition center, oral history archive, and community programming as we enter the new decade. We can't wait to see you again when the Coney Island History Project opens on April 5, 2020, for Coney Island's Opening Day!

Charles Denson

Executive Director