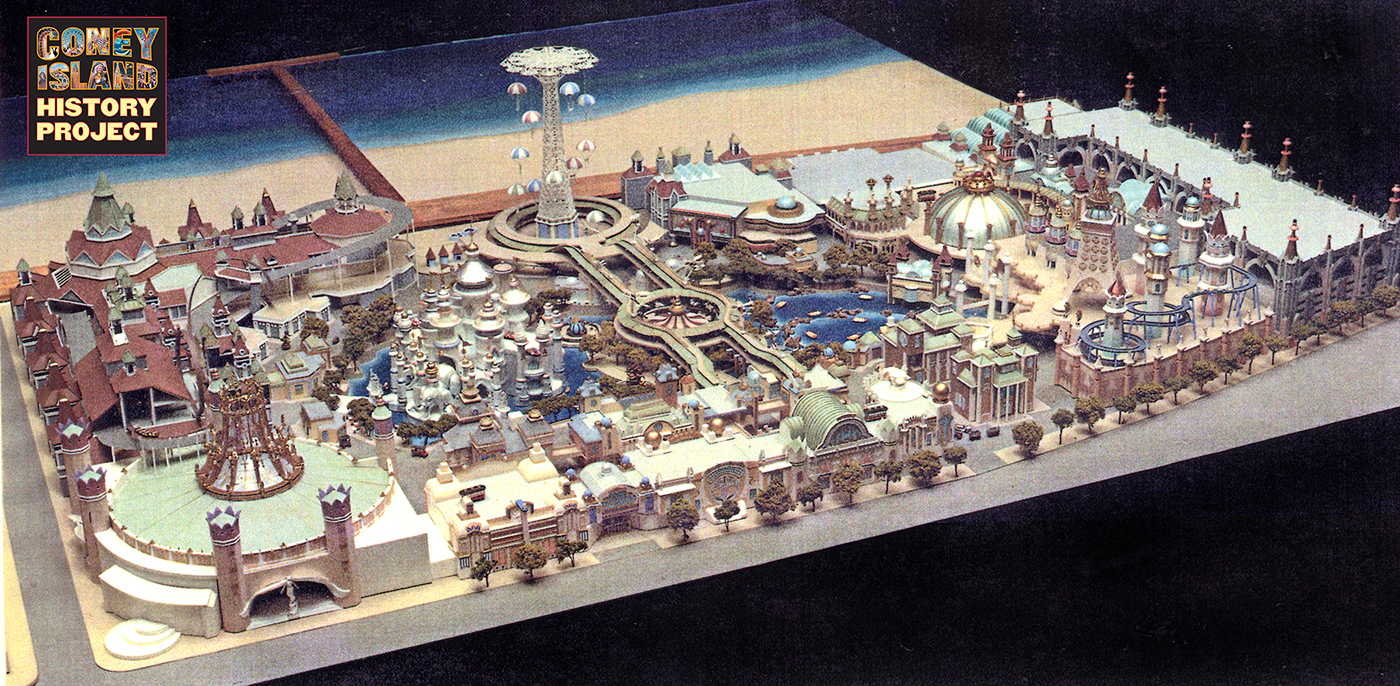

The following selection is from my book, Coney Island Lost and Found, published in 2002. As with most of the book, I used primary source research. During the 1990s I interviewed all the key people involved in the failed 1970s plan to bring casino gambling to Coney Island. This excerpt is taken from chapter 18, The 1970s: A Decade of Revolution. Above is Horace Bullard's model for his proposed development that included a casino. The story is copyrighted.

Casino Gambling in Coney Island, By Charles Denson

In 1976, casino gambling was legalized in Atlantic City, and for the next four years, casino fever gripped Coney Island. It seemed that we would be next. I remember the first rumors and then seeing a big billboard that the Coney Island Chamber of Commerce had placed at the Cropsey Avenue Bridge over Coney Island Creek. The sign read, “Welcome To Coney Island, The Perfect Resort for Casino Gambling.” It was painted on canvas with little starbursts and crude lettering. Yellow bumper stickers also began appearing. They read, “CASINOS FOR CONEY.” I became worried. Coney Island had enough problems, and I felt that if gambling came in, the amusement area would be wiped out, and the neighborhood wouldn’t benefit at all. Gambling would just bring more traffic and crime.

Coney Island and Atlantic City have a rivalry that dates back to the 1870s, when each competed for the title of preeminent East Coast resort. A hundred years after the competition began, both resorts had been surpassed by modern destinations like Miami Beach and Las Vegas. When the first Atlantic City casinos opened in 1978, speculators started snatching up Atlantic City beachfront property. In August 1979, the New York State Legislature formed the Casino Gambling Study Panel to investigate the feasibility of casino gambling. The panel issued a positive report that proposed a maximum of forty casinos in five locations: Coney Island, Buffalo, the Catskills, Long Beach, and Rockaway. Annual gross revenues from the casinos were projected at $3 billion. Lobbying efforts were launched to place the required amendment to the state constitution on the ballot in 1979 or 1980.

Coney Island property owners were delirious when Mayor Ed Koch predicted that Coney Island would pull in $120 million in annual revenues from table games and slot machines. Local businesses put their differences aside and banded together to fight for a common cause. The Casinos for Coney Committee was formed, and speculators began eyeing real estate in the area. For a brief period during 1979, the asking price for property on the Boardwalk rose from $3 to $100 per square foot. Ironically, the only person to profit from the proposed gambling was real estate speculator Oscar Porcelli, who bought the Washington Baths property from owner Fred Warmers and sold it to Horace Bullard for a substantial profit.

The Casinos for Coney Committee wasn’t aware that powerful forces were against them from the start. Donald Trump, son of developer Fred Trump, had casino interests in Atlantic City and wanted to protect them. Fred Trump did everything within his power to lobby the New York State Legislature into killing the referendum before it reached the voters. By the 1980s, any chance of gambling in New York State was dead. But for a few years, Coney could once again dream of competing with Atlantic City as the top East Coast resort.

Judging from what happened in Atlantic City, gambling would not have helped the local neighborhood but would have enriched some of the property owners. The old amusement area would have disappeared, and what kind of development would have replaced it is difficult to imagine. I interviewed most of the main players behind the Casinos for Coney coalition and asked them what it was like during the years of casino fever.

Charlie Tesoro, owner of Walter E. Burgess Inc., is the island’s biggest realtor, and his office became the first stop for the speculators who swarmed Coney Island. “It was crazy,” Tesoro said. “Limousines would pull up with guys coming up to the office from Las Vegas, in silk suits, saying, ‘Sell to us now, get us some property, we wanna get in!’ It was like a crazy house, like the gold rush. Steve Wynn pulled up in a limo and sent guys up to my office wearing flashy silk suits and solid-gold cuff links. Every other day you’d see limousines driving up and down Surf Avenue. It was wonderful. They’d sit at my desk and say, ‘Waddaya got? We want options on everything you got. Everything!’

“They wanted options because if gambling didn’t go though, they’re out. But if gambling went through, they’d pay triple the asking price for the property. They’re not so much gamblers when it comes to their money. They want you to be a gambler. I hadda laugh at ’em. People were even buying houses! A custodian came in from Manhattan and put every penny he had on three houses in Coney Island just because his cousin was a lobbyist and heard that gambling was gonna pass. Little guys were forming consortiums. They didn’t just want to buy in the amusement zone. They wanted the residential areas, Mermaid Avenue, West Fifteenth Street.”

Businessman Horace Bullard owned the Shore Theater building, considered a prime location for a casino. Bullard tried to sell his vision of a Coney Island gambling mecca to other landowners. His plan involved combining a new amusement park with the casinos. “At the time we started,” Bullard told me, “we knew that gambling had to be controlled. What we didn’t want was an Atlantic City. I was trying to convince people that they shouldn’t allow gambling to come to Coney Island unless it’s done right. I felt that you should have one casino and one hotel, and the revenue from them would pay to rebuild the entire amusement area. I came up with a plan for Coney Island and began lobbying the whole community. I formed what’s called an LDC—Local Development Company—and called a meeting. I wanted the board members that sat around the table at this meeting to be representative of Coney Island: the housing interests, Gargiulo’s restaurant, the Aquarium, Our Lady of Solace Church, the landowners, Astroland, Sea Gate. On the table would be a map of Coney Island with gambling being the primary issue. We could all fight for our different interests and come up with a solution, and by voting for what the board would pass, we’d have a direction that Coney Island could go with.”

Bullard held his meeting in a Manhattan hotel and unveiled an ambitious plan. It involved pooling together all of the property in Coney Island’s amusement zone, approximately eight square blocks, and building a large gambling/amusement complex. The entire facility would be above a massive parking garage at ground level. The property owners would sell their land to a newly formed corporation that would build the complex, and the landowners would be assigned an interest in the complex based on the percentage of land they had sold to the corporation. Bullard made an impressive presentation, but the landowners rejected it because they couldn’t agree on the percentages or the placement of the casino. They chose to go it alone and take their chances on obtaining options from the casino builders.

Jerry Albert, the owner of Astroland Park, told me that he felt Bullard was scheming to be the only one chosen to build a casino. “I don’t think that anyone was sure Bullard’s idea would have worked,” Albert told me. “When gambling was a hot item, everyone was talking continuously. But the feelings among the amusement ride operators weren’t friendly. They were competitive as to where gambling would go. If gambling was approved for Coney Island, it was going to be on only one or two sites, and everybody else would be out of luck. They’d have to do something else. The closer it came to having gambling in Coney Island, the more jealous people got. Bullard suggested that Astroland put in amusements, and they’d build us a parking lot underneath the amusement park. But Astroland already had the amusements. Horace had an architect and was putting out renderings and drawings, and he held meetings to explain his concept of how things should be laid out. But it was always with the idea that Horace would be the one to get the gambling.

“Every day, there were rumors that options were being sold on land in Coney Island. We were in negotiations with one of the largest casino owners. The Golden Nugget was negotiating for an option on the Astroland property. I did not get the option for one reason. It was Labor Day weekend. The biggest casino owner in the United States was flying up in a Lear jet to sign the option agreement for $12 million. My lawyer said, ‘It’s Labor Day weekend, Jerry. Why must we go through with this meeting? Everyone is busy on Labor Day weekend. If you wait until after the weekend, I can get you $17 million.’ And I said, ‘The hell with it. I’m satisfied with $12 million.’ I got into an argument with him, so we put off the signing till the following weekend. Guess what happened? Governor Hugh Carey held a news conference on television and said, ‘As long as I’m governor of New York, there will never be gambling, because gambling is basically bad for the state.’ After he made that speech, that was the end of gambling.”

The merchants of Mermaid Avenue were big supporters of the casino plans. Coney Island businessman Lou Powsner had just given a speech at a governor’s hearing at the World Trade Center in 1978 when he received a call from a representative of the gaming industry who wanted to discuss Powsner’s analysis of casinos in Coney Island. “I asked him where he was from,” Powsner said, “and he said he could not divulge that information. We later found out he was from Caesar’s World. I told him that downstate, Coney Island with its tremendous Boardwalk was ripe for development. I also pointed out that we had an abundant labor market nearby crying for jobs, a sea of unemployment.

“We formed a local group and convened five times. Our slogan was ‘Casinos Mean Jobs,’ and they did. I was up to Albany five times. I went with Charlie Tesoro and with Hy Singer, who had hoped to turn Stauch’s into a casino. The Russo family, owners of Gargiulo’s restaurant, was also in the coalition. I met Bullard a couple of years later, when he held a meeting in a high-rise castle in Manhattan and we went over his plans, which featured an amusement park. It was a tremendous proposal.”

The gambling resolution had a good chance of passing, but just before the state legislature was getting ready to vote, New York State Attorney General Robert Abrams held a press conference and said that he wouldn’t want to see happen to New York what had happened to New Jersey, with crime and prostitution. The vote never made it to the floor.

“Abrams was a stooge for a developer who didn’t want gambling,” Powsner said. “At that time, Donald Trump was a virtual unknown. On one of the trips that we made to Albany, Jerry Albert had a magazine called Gaming. In a sidebar, it said Donald Trump, the son of a New York developer, had under-water land in Atlantic City and was hoping to get the funds to build a major casino hotel. He got the funds and put up Harrah’s Trump Plaza. We went down to defeat because Donald Trump had devised our defeat.

His last move was to get together with one of the Tisch brothers and Sam Schubert, the theater owner who said that the casinos would destroy New York’s theater district. And State Assembly Speaker Stanley Fink wouldn’t let the bill come to the floor. It was Trump who killed it. It was all political, and it destroyed New York’s opportunity to be the gambling capital.”

Charlie Tesoro told me that he agrees with the theory that the Trumps sabotaged the casino resolution. “We had everybody convinced that gambling was coming. We went to all the congressmen and senators, and they were all for it. Then Fred Trump comes in and says to them, ‘You want the Mafia? You want prostitution?’ We had no idea he was already in Atlantic City. And little junior there, Donald Trump, was heavily against gambling in New York. His old man didn’t like the way it was gonna be handled.

We did not have enough money, and the big money was against us. We had a slush fund of $50,000 to support it, and Atlantic City had $500,000 to fight it. We had busloads of supporters, we had signatures on petitions, and the trade groups on Mermaid Avenue were for it. Gambling was the only thing that would have developed the area. It would’ve brought in hotels and millions of dollars in investment money. I couldn’t believe that New York State said it couldn’t be controlled. Meade Esposito, Democratic leader of Brooklyn, told the legislature, ‘Don’t vote for it.’ They were dupes of Trump and Atlantic City. Nobody knew that at the time. You didn’t know your enemies.”

In the end, gambling proved to be a bad idea. By the time it reached the legislature, New York law enforcement could see the damage in Atlantic City and the inability to keep out organized crime. When a Coney Island landlord on West Fifteenth Street assaulted a tenant and tried to evict him, the incident was played up as an example of “gambling fever.” Everyone was saying that the landlord wanted to evict the tenants so that he could sell the building to speculators.

Even before the casino resolution came up for a vote, corrupt politicians were asking for bribes. Charlie Tesoro recalls several incidents. “There were a bunch of congressmen and a couple of wise guys who all wanted 6 percent. ‘You want the gambling?’ they’d say. ‘Sign these contracts saying that such-and-such law firm will handle the case.’ You wouldn’t believe the corruption! These guys would come in and say, ‘If you don’t sign this, it’ll never even pass the first session.’ Nobody wanted to pay, but we didn’t get gambling anyway.”

Jerry Albert has no regrets and feels that Coney was better off without casinos. In 1999, I asked him if he thought the casino idea would ever be revived. “Gambling will never come back,” he told me. “Every once in a while, it rears its ugly head, but definitely it will never happen, because Atlantic City is too powerful, and Coney Island, as far as I’m concerned, has become better every year, and I’ve been in Coney Island for forty years.

“The end of the 1960s was the low point. The trouble is that a lot of people who are in business in Coney Island have never invested any money and have let their property deteriorate. They were living with thoughts of gambling coming to Coney Island, and it was like gold fever. All the competitors basically had a shortsighted view of the situation. They were convinced that gambling was going to happen.”

Horace Bullard seems to agree with Albert. “I don’t believe that Trump stopped gambling,” Bullard said. “I believe greed stopped Coney Island from getting gambling. Landowners’ greed.”